|

|

[ Back to the V.I. Literary Archives Menu | Back to Part I ]

Siew-Yue Killingley, the author of the excerpts below, hereby asserts and gives notice of her moral rights of paternity and integrity under sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of these excerpts taken from her unpublished and published works. All rights reserved. No part of these excerpts may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright holder, c/o Grevatt & Grevatt (see address in the catalogue in Part I). Preliminary enquiries may be made via Chung Chee Min, to whom permission was granted on 16th March 2000 to reproduce these excerpts for the Victoria Institution Home Page. STORIES A QUESTION OF DOWRY EVERYTHING'S ARRANGED

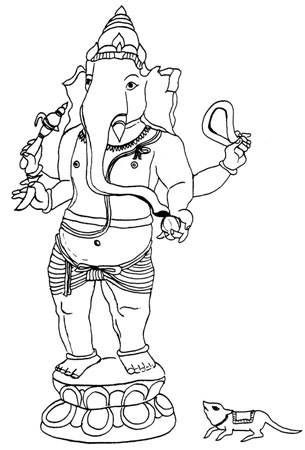

8) A story written in the early to mid-1960s; published in Tenggara, no. 1, 1967, Rayrirath (Raybooks) Publications, Kuala Lumpur, pp. 38-51, and in Twenty-two Malaysian Stories: An Anthology of Writing in English, selected and edited by Lloyd Fernando, Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) Ltd., Singapore, 1968, pp. 185-205. Corrections of some minor printing and other errors in the published versions have been incorporated here. Dear Auntie Sally, This reply appeared in the papers at the same time as a letter for Rukumani from Devanayagam. Amy rang up and told Rukumani there was something for her. Rukumani tore out the bit in the paper where her letter and Auntie Sally's reply had appeared and flushed it down the lavatory bowl. Then, telling her mother that she was going to Amy's to study, she took her copy of Benham's Economics and took the bus to Greentown. I wonder whether you are thinking of me as often as I am thinking of you, dear Ruku. This thought occurs to me often, especially when the moon is full. It is a universal symbol of our love, the spiritual moon. On the way to a show with my friends, I often think of you and I feel glad that you can be trusted not to be like other girls who are too modern and like going for shows with boys. I know you are waiting patiently for me. Ever your faithful 'What he say? Secret ah?' Inquired Amy. I think of you very often but maybe you have forgotten me. I received your letter about your proposed marriage. If you agree to that I cannot do anything to prevent it and I hope you will be very happy. But I shall never forget you and hope that spiritually we shall remain close like brother and sister. I too have some sad news to tell. My parents want me to marry a distant relation whom I have never met. I think he is going to be a B.A. but they don't mention his name. I have great troubles here and wish you could save me. Why is it that we have to be separated and bear such terrible burdens? Devanayagam was quite touched by Rukumani's devotion. He felt a little guilty himself. His own objections at home had created such scenes of domestic strife that he had persuaded himself into thinking that it would be heroic to 'give up his true love for the sake of the family'. Therefore, before going away he had told his parents, 'All right, all right lah! Stop bothering me and leave me in peace to study and I'll marry this girl,whoever she is.' My Son, AN OVER-DILIGENT CAT 9) Written in 1979 for children up to the age of eleven to teach them about Indian culture, from A Handbook of Hinduism for Teachers, p. 10; see Catalogue, no. 7. THE BIRD WITH GOLD DROPPINGS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM 11) From A Handbook of Hinduism for Teachers, pp. 59, 53 (also from Hinduism Iconography Pack, pp. 2, 8), 70, 65; see Catalogue, nos. 7 and 8. Ganesha © Siew-Yue Killingley 1980 He is the elephant-headed lord of obstacles. He holds an elephant driver's goad, a noose, a cake which he sniffs, and one of his tusks, which has broken off. The animal he rides on is a rat. She is playing the vina, holding a string of beads and a book, and is accompanied by her goose. He is Shiva's bull, decorated with chains and bells. He is milking a cow while she licks her calf. REUNION .............................. Everyone called my nurse Ah Gau because she was the ninth child in her family. I called her Gau Chieh. She had always been there ever since I could remember. I knew her smell, and the feel of her cool, pale skin, so unlike the colouring of the rest of the servants. Then one day she vanished. When I saw her again, after I'd been to school for five or six years, she was married and had three boys of her own. She was much stricter with them than she had ever been with me. My mother's old nurse, whom I called Poh Poh, although she was not my grandmother, had come with us on holiday to Ipoh. In those days there were still twenty-eight miles of winding road before you reached Slim River. Poh Poh took me to see Gau Chieh. They were related in some way. Mama had given Poh Poh some money and presents for Gau Chieh and her children. I noticed that when the youngest boy, a baby, held up his arms to be carried in the way that I had often done in the past, Gau Chieh took no notice at all. I would've been very annoyed. Also, she let her children open up peanut shells for themselves instead of doing it for them and popping the peanuts into their mouths. [

Part I - The Poetry of Siew-Yue Killingley]

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1965; © Heinemann 1968, the author retaining the right to include the work in any collection exclusively of her own works two years after 1968.

There was much excitement in Mrs. Ramachandran's household. The daughter of the house, Sivasothie, was going to be engaged. The festive air was laden with the spicy smell of curries and wadés sizzled in the kwali saucepan. The young lady of the house, as befitted her present condition, assumed a calm pose amidst the general bustle and noise. Mrs. Ramachandran flew here and there, as fast as her hundred and sixty pounds would allow her, and helped with her commanding suggestions.

'Don't put too much coconut-milk in at once, Ayah! It's got to go in by stages. The last bit - the richest part, must be kept to the last! Now, Tamby, go out and play - but don't dirty your shirt. What will Uncle Thiruchelvam think if you're dirty?'

Just then, Mr. Ramachandran came into the kitchen and beckoned to his wife. She went out dutifully, for she managed her husband well- obeying him in the little things with such readiness that he thought himself lord of everything else as well. In their room, Mr. Ramachandran asked his wife where she had put the chain which they were giving their daughter as a personal present. Mrs. Ramachandran went up to her cupboard and unlocked an iron casket in which were many glittering trinkets. From the mess of glitter, she extracted a heavy gold chain carved rather much in detail. She sighed with contentment.

'Thiruchelvam's mother and his double-tongued sister can't possibly mistake the value of this necklace. I'm glad we decided to give this. It can be kept for her daughter when she gets married. Thiruchelvam's mother! What a grasping woman she is - so surprising that she should be one, because her husband earns so much a month. Her son is more like his father, thank goodness! I'm sure she takes most of his salary now - but then, doctors always have a lot - though he'd better think twice before giving too much to his mother now, since he's going to have a family of his own soon. Oh, Ramachandran! You must have a talk with that young man some time and give him a few helpful hints on how to save for his future family. You see, he's got to realize that his sons must have a good education, and that his daughters must have enough dowry. These young men never realize what they should do for their future and for their families.

'Well, Ramachandran, I leave all this to you - you can handle everything so well, especially young people, I always say! Anyway, you have done well by our daughter! Twenty thousand dollars is not to be scoffed at - that's more than I can say for what Thangathurai gave his daughter when our son married her - and she had only passed her Form IV too! I was never for that match - but Arul has always been a stubborn and unfilial boy - how could he insist on choosing his own wife? Well, that's past. Now, I really must leave you. There's so much work to see to.'

Mr. Ramachandran had been trying to get a word in, and when his wife paused for breath (for she was really going to continue), he grabbed his chance.

'We have to return the necklace.'

'Return it? Why, what will Thiruchelvam's mother and -'

Mr. Ramachandran raised his hand.

'There's something which I've wanted to tell you for some time, but I didn't want to worry you. We can't pay for the necklace. Do you remember the land we were going to sell to get the dowry and money for the necklace?'

'Oh, be careful, you old man! Do you want people to think that we have no money for our daughter?' Mrs. Ramachandran hissed in fierce whispers. Then, continuing in a more normal tone, she inquired loudly, 'Which piece of land do you mean? My father gave us four for my dowry, and our second son received three as his wife's dowry.'

'Come now, wife!' remonstrated Mr. Ramachandran. 'Don't you remember? We have only one piece of land left from your dowry - we sold the other three for our third and fourth sons' weddings. You asked me to do it yourself. As for Anandakrishna's land, that belongs to him, and he's already rented it out to some householders in order to get cash for his eternal drinks.'

Afraid of further secrets being revealed to prying ears, and being anxious to save her family's face, Mrs. Ramachandran motioned to her husband to drop the subject. However, Mr. Ramachandran continued.

'About the land, I'm afraid it is impossible to sell it at a quarter of its former price. You see, water has been seeping out from some well for about ten years, and so the land is now too marshy for house-holding. Unless we were to drain it, no one would buy it at our sum.'

'Are you insulting my poor father? He give me a piece of sodden land? Impossible! Oh, if he had known what sort of a son-in-law he was getting, he would have made a wiser decision. But I shall have a better son-in-law who'll not depend on his wife's dowry. He's a doctor, and he has his own income!'

With that she stalked out, after having locked the gold chain securely in its container again. Mr. Ramachandran looked worried, but resigned. He always found himself at a loss for words when his wife was most eloquent.

Mrs. Ramachandran called to her daughter, and the latter came dutifully from the chaste quiet of her bedroom.

'Sivasothie, you are a very lucky girl. You'll have a doctor for your husband - and Mrs. Muthu will have a fit from envy. But you are so much better than her daughter. Now! Thiruchelvam is coming in half an hour, and - well, you're nicely dressed, I see. Do pin up the jasmine flowers - they're too drooping on your left side - there! That's better - oh, why did you move? Look what you've made me do. You've made me knock two off - no matter! This looks bette - not so crowded. He loves you very, very much - his father told your father so.'

Sivasothie looked shy and glanced away with a modest droop of the head. Tamby yelled:

'Peria akka! Uncle Thiruchelvam has come to see you! Peria akka! He's waiting for you in the hall! I've told him you've been waiting for the last two hours.'

The two women were horrified. Mrs. Ramachandran snatched the happy Tamby as he danced into the room and spanked him hard.

'Silly boy! Don't shout those fibs. Why, your sister has been hard at work in the kitchen' (this very loudly). 'Just because she looks so fresh and tidy, it doesn't mean she wasn't working. Do you think she's so lazy as to sit and not do anything? Go out and play.'

Tamby hurried off, surprised and unbelieving. Sivasothie and her mother went out into the hall, where the former, permitting herself the most modest of glances at her ardent pursuer, and permitting him to receive from her the merest minimum of shy smiles, shuffled discreetly and retiringly into the kitchen.

'Good morning, Auntie', said Thiruchelvam, 'I've come to see Uncle Ramachandran. He rang me up this morning.'

'Please sit down and I'll get Sivasothie to fetch you a drink. Do taste some muruku. They're newly-made and crisp Sivasothie is so clever - but of course', she added coyly and slyly, 'you know that! Sit down! Sit down! Make this your home, though it's not comparable to yours, of course. And how is your dear mother? I must go and see her soon - we'll have so much to talk about. But that's not surprising - we have the same interest - and that, of course, is your happiness. Now, do sit down and I'll ask -'

'No, no, please don't bother. I'm very busy, and I must see Uncle Ramachandran and go. Do call him down, please.'

Mrs. Ramachandran knew when not to cross a person and she gave in with good grace.

'Well, I'm sure you have a lot to discuss; so I'll fetch him for you.'

Thiruchelvam sat down awkwardly, attempting not to show his annoyance. What a silly mother - her daughter's modest airs - did Mrs. Ramachandran have them when she was young too? Well, a man had to have a wife, so why not have one with a reasonable dowry?

Mr. Ramachandran came in with his wife, and after further pleasantries on the latter's part, she departed for the kitchen. Mr. Ramachandran then proceeded to tell his future son-in-law what he had already told his wife earlier. Thiruchelvam, having less faith in Mrs. Ramachandran's father, believed the news about the devalued land.

After Thiruchelvam had left for his dispensary, Mr. Ramachandran had to let his wife and daughter know about the changed situation.

'Well', commented Mrs. Ramachandran stoically, 'there's more than one doctor in our community, and it's up to you, Ramachandran, to do your duty as a father.'

Sivasothie went into the kitchen, her head bowed modestly.

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1965; © Heinemann 1968, the author retaining the right to include the work in any collection exclusively of her own works two years after 1968.

The last day of term was always dreary for Rukumani and Devanayagam. They had to say goodbye many times over before going to their respective homes, his in Lipis and hers in Ipoh. This being their last day together, they were also tempted to do rather dangerous things, such as walking back to the Third College and sitting in the very public lounge where fellow students who were remotely related to them and Ceylonese parents who came to fetch their offspring home would see them. Going to more secluded parts of the campus was even worse although it meant less chance of being gazed at, for if they were seen by people who knew them and their families, they would be accused of making love in quiet corners. It was better to sit in public and take the risk of being seen by family friends, some of whom might just casually mention to their respective families, 'Your son is a friend of Ruku's' or 'Your daughter is getting some help in her work from Deva, it seems. Saw them in the Third RC lounge', and leave it at that.

The long vacation stretched wearily before them both. Devanayagam thought of coming back for the last two months or so to read in the library, but they both knew that it was hopeless for Rukumani to do that. Like most people, her parents had the idea that terms at the university were like school terms; also, that if she went back to stay at the hostel, she would be open to all sorts of dangers and temptations, since there would be no classes to attend and therefore no lecturers to keep an eye on her chastity. At the same time they liked to pretend that Rukumani was 'too spiritual to know anything about sex', and that topic was never mentioned at home. The time for her marriage to be arranged would soon come and she would find out all about that after she was married. Marriage was such a spiritual thing, really, that if sex were brought into it, it would give her the wrong ideas, such as those of the Modern Girl. Sitting in the lounge, watching the distracting and excited girls rushing by with packed cases, longing to go home to some decent food, Rukumani asked Devanayagam,

'This time you think you can write or not? can send to Amy's house, what. My mother likes her mother. I can easily go there to get your letters. But I think better you don't put my name outside. Can just put "Miss Amy Wong". She knows your writing and won't open.'

'I think so can', replied Devanayagam, 'but helluva difficult, man. See ah, my sisters, brothers all, running all over the house, and if I write they all ask if I'm learning and want to look. Also ah, if I go to post letter, that clerk at the post office can see me. He's a joker, so sure tell my father I send love letters. But still, try lah!'

Rukumani was a little piqued. It was all right for Deva to be put off writing to her because he could go out to shows with his friends. Moreover, he had the tail-end of the vacation to look forward to, when he could come back to the U and not have his family on top of him. She would have to suffer all sorts of deprivations in Ipoh.

'Suppose you tell them you want to go for shows. Then can simply go somewhere and just scribble a note to me. Don't think I'm so hard up ah, but since I suffer for you, at least you should write to me when you're free.'

'Okay, okay lah! Not that I don't want ah, but very difficult. Also, if you know that I love, then should be sufficient what; what for want to write the whole time?'

They both felt uncomfortable. Being surrounded by lots of people, they both said things without being sufficiently careful not to hurt, and their mutual fear at their daring clandestine affair could not but be obvious, although each considered it a betrayal to reveal this fear to the other. In the end, they decided that it was time for them to part for the vacation, both feeling depressed and irritated, envying the more fortunate couples, especially the Chinese ones, who went about openly holding hands.

Rukumani had to get a taxi to the railway station to catch the afternoon train back to Ipoh. Devanayagam was to get a taxi to the Ampang Street bus station to catch the East Coast bus. They silently wished that they could go in one taxi, first dropping Rukumani off and then letting Devanayagam go on to Ampang Street. Neither mentioned it in case they were seen in town and that would be extremely dangerous, since townspeople were certain to let their parents know if they were seen together, whereas university people could sometimes be relied on to keep their mouths shut. They remembered also Rukumani's uncle on her mother's side by marriage who was a C.C. in some branch of the Malayan Railways, and although he had seen Rukumani just once at Deepavali, he remembered her very well and always referred to her as 'his niece at the U'. Fearing, therefore, to worsen the already tense situation between them, they left each other to finish packing and left separately for home.

The train compartment was full of sleeping people, mainly women with babies. There was a Chinese woman who had a veritable brood with her, and she was having an argument with the ticket inspector, who said that her children could not all share one ticket. Rukumani was too engrossed with her own problems to follow the argument to its end, but after a while the inspector seemed to have given up arguing, because he left with a shake of the head. Seeing that the woman seemed rather harassed about her children, who were spilling all over two seats, Rukumani smiled at her and edged nearer the window so that one of the children could come and share her seat. To her great annoyance and some shame, the woman prevented one of her children from leaving the overcrowded seat with a muttered 'Kiling mui'! After this insult, Rukumani took no further notice of the woman and her litter, but reached for her book bag on the shelf, took out Benham's Economics and read the chapter on 'supply and demand' without any interest but with a comforting sense of being learned, while the silly Chinese children stared, picked their noses and bullied one another.

As they neared Kampar, someone passed Rukumani on the way to the lavatory and exclaimed, 'I say! Diden know you also on this train. If not, sure I come and keep you company, man. Train journey boring like hell.'

With pleasure, Rukumani recognized her class-mate Johnny Chew, who was regarded with respect as the 'walking economics bible'. Not only did he know all the impressive technical terms used by overpowering economists like Benham, Hanson, and Keynes, he also remembered and often used in his essays economic terms coined by the lecturers, thereby earning their respect and a reputation as a dedicated scholar. He also had a knack of coining terms himself which had the proper ring of a technical word, and this earned him greater fame in the department. Everyone betted that he was 'sure going to get first class'. They chatted for a bit, Johnny sitting on the arm of Rukumani's seat, to the disapproval of the Chinese woman with the brood. She passed Rukumani some dirty looks when Johnny excused himself to go to the lavatory, and when he came back again after that, the woman looked displeased and aggrieved. For her part, Rukumani was a bit apprehensive that Devanayagam would hear about this in case he misunderstood the circumstances or objected to her being so free with a male fellow student. Still, she was so bored and fed up that she decided to risk anyone's displeasure in order to shorten the journey.

'So after Finals what you intend to do?'

She asked the current question of the year.

'Oh, myself? Sure fail, man', came the classic answer in an unconvincing tone.

'Eh, don't joke, man. I think you sure become Assistant Lecturer in the department, if not Lecturer.'

The flattered Johnny was led to reveal his real ambition to become a Sales Representative in one of the big firms.

'Not to say what ah, to become a lecturer is all right. But think of it ah, now we give them helluva headache; if myself become one, sure die, man. Sure, sure, got prestige and all, but can't be boddered, man. Too much trouble. Better still become Executive. Supply and demand what. Know that means know everything. Also ah, you know what I can take if I get fed up? Can take that what you call Ford pills for Executive Fatigue. Then also can easily save on big salary, can buy nice Jag and take girl friends for drives. Can easily tackle and get a good wifie too, but that better not want too soon, because why? Trapped lah! After, they want this want that, then worse headache than marking essays, what you think?

It was not that Rukumani had heard this for the first time, since Johnny was always saying these things over and over again. Today, she listened partly out of having the rest of the journey empty in front of her, and partly because she could not help envying Johnny his freedom. She dreaded the end of her university career as it meant that the preparations for her wedding to whomever the family were at that moment deciding for her would be intensified. Somehow, the journey was suddenly over and they were still talking about this and that. With a shock, Rukumani realized that the head which appeared at the window belonged to her father. Johnny was not perturbed.

'Hello, Uncle', he hailed most heartily, 'your daughter and myself were having a most interesting talk.'

Two sorrowful eyes looked steadily at Rukumani for signs of shame.

'This is my father, Mr. Sambanthan. He's the C.C. in the Ipoh branch of the -.' Rukumani mentioned some department that Johnny had never heard of. After a few more exchanges, Johnny left for his home in Sweet Dreams Housing Estate while Mr. Sambanthan led Rukumani to a taxi to take them to Lovely Housing Estate.

'Who that young chap?' Mr. Sambanthan asked, trying to keep the note of suspicion out of his voice.

'I told you at the station, Pa. He's Johnny Chew, and he's in my class. He often helps me with my work. He's very brilliant.'

Mr. Sambanthan felt a little relieved.

'You know where his father working?'

'Income tax.'

'Ahhh!'

The respectability of Johnny thus settled, they continued in silence to Lovely Housing Estate.

Rukumani had a younger sister called Baby by the rest of the family as well as by other people who were not in the family, but who knew them rather well. This Baby was approaching her eighteenth year and was preparing to enter university the following year, but the childhood name had stuck, to her embarassment. Besides this sister, whose real name was Susheela, there was a younger brother of twelve called Boy, although again, he too had another name, Nadarajah. Rukumani was not quite sure she could trust Baby with her secret, but she knew for certain that if Boy knew about it, her parents would be upon her in no time, as he enjoyed being their favourite and indulged in unconcealed tale-bearing. In addition to her parents and brother and sister, the tiny house in Lovely Housing Estate also housed her grandmother on her father's side, who always held forth on the degeneracy of young girls nowadays. This often included Rukumani's mother, who, indeed, could never hope to be a young girl again except in the next incarnation, perhaps. Rukumani's mother, in order to shift some of the blame from herself, sometimes tried to get her mother-in-law on her side by lamenting loudly that the young generation of daughters was becoming too modern, and shouted for either Baby or Rukumani to fetch her things which were nearer her than them, just to test their obedience and to show her mother-in-law that she had her girls in hand. In addition to the members of the household who were permanently living in the house, there was a periphery of aunts on both sides, nieces, and stray relatives from Sungkai Estate or Menglembu who sometimes came to stay, especially around Deepavali, when the tiny house became even more noisy and over-crowded, like the little poutry-run in the back garden. Babies whose parents had left them behind in the house while they visited yet other relatives in Ipoh became the charges of Baby or Rukumani, since their mother would often accompany the visiting relatives on their calls.

It was way past nine o'clock by the time Rukumani and her father arrived home. Some visitors were staying overnight, obviously, as Rukumani could see some half-naked children sprawling on the concrete walk outside the house and eating some very sticky rice sweet. Their parents were inside, talking in loud tones to Rukumani's mother and grandmother. It was really the women who were doing most of the talking, the men adding a grunt or two when their opinions were asked. Rukumani felt that she was inevitably home when she heard the shrill mixture of voices which sounded more as if they were quarrelling than conversing. When she had walked past the gaping children with her luggage, Rukumani appeared at the door and greeted her grandmother, mother and the visitors. She did not remember any of the visitors, but since there were three women and one man, she just said 'uncle' once and 'auntie' three times and wished she could have a little food and then go to bed. Her mother was in a lively mood that night. Drawing her sari round her ample frame, she said to the company, 'You remember Girlie, don't you? do you think she has changed?'

'Getting near marriageable age', remarked one of the women.

'Better you don't put ideas into young people's heads', advised the man, who was probably the husband of the woman. 'When we were young, our mother never mentioned the word "marriage" to any of my seven sisters until two days before they were to be married. Everything fix first, then talk. If not, all the young people think of is girl friends, boy friends, what for?'

'Ah', sighed the wife, 'but nowadays different. Especially when someone like Girlie, so pretty, going to get university degree and all, better to fix everything while still possible to control. Once they grow older, just try to control, and see.'

Here the company sighed, and there was a momentary silence as they remembered this woman's young daughter whom she had loved so much that she had allowed her to enter the university several years ago, even though she was a girl. This ungrateful child, whom she had looked forward to comforting her old age with dutiful attention and obedience, had proved a disgraceful and shameless hussy by rejecting a match with a promising lawyer who was willing to accept a cheap dowry because of her BSc, and had run away to marry a class-mate of hers who was a Chinese Arts graduate. Not only did this prove her shamelessness, it certainly showed everyone how stupid she was to offer herself to a mere BA. Everyone was too kind to voice their thoughts, although those not involved secretly felt self-satisfied that no such misdemeanour had occurred in their families. Rukumani was feeling too tired and too disgusted at the reminder that she was 'Girlie' at home to notice much that was happening. After some further comments on her looks and that she must be too proud to know them now, the visitors collected their scattered children and left.

'Come and take some food', said Rukumani's mother after the visitors had left. 'You're a lucky girl. You know why Auntie come to see me? Never mind, take first, talk afterwards.'

They sat down together in the kitchen. Boy was in bed, but when Baby, who had been washing up in the kitchen, tried to join in, she was shooed away by her mother.

'Go, go, do your homework. How you think you can be like Akka and go to the M.U. if you don't study? You think very easy to feed you all? Better not make me show temper, I tell you.'

Rukumani was silent over dinner. The rest had eaten, and she did not really enjoy the cold rice and curry, but ate it out of boredom. Then, through her half-sleepy mind, her mother's chatter made some sense and she felt alarmed. She realized the significance of the visit they had just received. By some tenuous relationship, she was a very distant cousin of the man who had spoken to her, since his wife, the long-suffering mother, was a sort of cousin of an aunt of her mother's. This man had a relative whose son was at the moment in his final year at the university, and they had come at the invitation of Rukumani's mother to see about the possibility of there being a match between Rukumani and this young man. It was unusual for the representative of the would-be groom to visit the family of the girl, but in this case, Rukumani's mother proudly hinted, they were in a strong position since they were richer than the other family, although this should not put Rukumani off, as her husband-to-be would have a high income as soon as he graduated. 'At least Civil Service Super-scale'. She also reminded Rukumani of her duty to her family in setting a good example to Baby, and, when she was married, she was to be sure to coax her husband to live in Ipoh and not in his home town, where his family would surely eat up all his income, grasping wretches that they were. Rukumani did not want to believe that all this was really going to happen, so she just kept quiet and went to bed. Baby, who had retired somewhat earlier, was not asleep yet, and tried to tell Rukumani in whispers what had been cooking at home during the last term when Rukumani had been away. Although Rukumani wanted to keep her dignity as Elder Sister intact and not lose any authority over Baby by descending to whispering secrets with her, this time the sense of danger to her own arrangements made her swallow her pride a little and listen. What Baby told her confirmed her fears as she realized that her parents, especially her mother, had been making arrangements for a long time, and that this proposed match was no mere whim of her mother's. She began to feel rather cross with Baby for confirming her fears, and kept a resolute silence, refusing to comment and finally succeeding in fooling Baby that she was asleep.

The vacation was long and dragging. Sometimes Rukumani went shopping with her mother or with a visiting aunt. These trips gave her no pleasure now. It had not thrilled her to be taken to John Little's, where there were gleaming modern glassware in one department, ready-made dresses and high-heeled shoes in another, and so on through countless high-class departments. Nobody in their house wore frocks or high-heels. Anyway, the things at John Little's were too big for them, and the girls a bit saucy whenever they did try on something for the thrill of it, for they always remarked haughtily, 'Cannot fit, lah! All these European size. Better you go to Hugh Low Street shops.'

This sort of thing always angered Rukumani's mother, and she would annoy the shop-girls further by asking for something as unlikely as nylon stockings. Sometimes she also let drop statements like, 'My daughter need this to go back to M.U. when long vac over.'

This sometimes earned her some respect, but at other times did not create any stir. The shopping trips usually took them to the Sari Emporium, where Rukumani's mother and aunts fingered lengths of Senior Kashmir, rejecting saris made of Junior Kashmir, no matter how pretty Rukumani thought they were. This was because they said that Junior Kashmir could be recognized as something inferior from as far away as twenty yards, whereas Senior Kashmir 'got class'. The shopkeepers, anxious to please, hounded them on the pavement even before they entered the shop with repetitions of 'hullo, yes?' Rukumani knew that all this shopping and shop-gazing were leading up to the one thing she dreaded, and she lived in a state of apprehension and boredom. She decided to write to the papers, and her letter appeared in the 'Auntie Sally' column together with Auntie Sally's reply:

I am a girl of twenty-two and am in the final year at the university. I am madly in love with a boy who lives far, far away. My parents do not know of my romance. They want me to marry someone whom I do not know. At times I think of committing suicide but I am not sure how to kill myself. My boy friend has not written to me yet and does not know of my sorrows. I fear I shall make him kill himself too if I kill myself. Sometimes I think of becoming a nun, but I am not a Christian. Please give me some advices as I do not know what to do.

Broken-hearted

Dear Broken-hearted,

Silly girl! Do not think I'm heartless. I am always willing and happy to help a deserving case. But look at you! have you no sense of shame or gratitude? I do feel sorry for your poor parents who have suffered to send you to the university, and this is your way of repaying them, with ingratitude, deceit, shameless behaviour. You are too young to think of boy friends. The time for that will come after your studies. You are lucky that your parents love you so much and are thinking of your welfare. Think of others less fortunate than yourself. Count your blessings and accept your parents' choice of a husband for you. Mother knows best! Your parents have your welfare at heart.

Love from

Auntie Sally

Amy was quite ecstatic when she saw Rukumani. She took her up to her room, chased her younger sisters out of it, and locked the door. From under a chest-of-drawers, she took out her copy of Benham's Economics and withdrew from it a letter. Then she discreetly pretended to read her book while Rukumani read her letter. Rukumani wanted to prolong the pleasure of anticipation by just looking at the envelope for some time, but Amy became rather impatient with her, in spite of not wanting to give the impression of intruding. Amy kept glancing up from her Economics at the hesitant Rukumani and at last grunted, 'Open, man! What for want to keep on staring-staring?'

Rukumani did at last open the envelope and took out her love-letter. 'Dearest Darling Ruku', it began. Rukumani could feel a funny, not unplesant, sensation down her spine. Devanayagam was never so ardent in speech as in letters. 'Dearest Darling Ruku' was quite a change from his spoken 'eh, Ruku', or at the most, 'Dar' or 'D', which were abbreviated endearments which they and other courting couples used in their tender moments. She read on:

There is something I must tell you. Please do not worry, for two reasons. First, let me tell you the news. My parents have arranged a marriage for me with a distant cousin. They say she will give a big dowry and that she is very beautiful. Moreover, she is going to get a B.A. and is very fair-skinned. Why you mustn't worry, let me tell you first. I don't want to marry this girl because I love you. Secondly, if I am forced to marry her, you will know that it was not my own wish and that spiritually we belong together. But do not worry. After I leave the U, I shall be able to get a job and we can get married. I have hinted very strongly to my mother, father and uncle that I may want to choose somebody myself, and this made them angry, so I'm keeping quiet for a time. Please do not write to me or I shall get into trouble.

When I get to the hostel for the last two months of the vacation I will write again and then you can reply my letter.

Deva

'Nothing much lah.' Rukumani tried to look unconcerned, and after an hour or two's gossip, returned home.

How the long vacation went past Rukumani was never quite sure. She was often apprehensive, thought of writing to Auntie Sally again, started a few letters outlining her desperation and tore them up, flushing the pieces down the plumbing. She was tempted to write to Devanayagam but feared his displeasure if she got him into trouble. Once or twice she tried to take Baby into her confidence, but that might mean losing her authority as the elder sister. Boy proved a continual source of irritation as he liked rummaging in her boxes, which she kept under the bed she shared with Baby, and Rukumani was always in fear that Devanayagam's love-letter would one day be exposed. Her mother and grandmother kept at her about her arranged marriage, and whenever women relatives visited they were consulted, and in their turn gave advice. The most popular saying supplied by these advisors was that nowadays girls were 'too modern', and had better be married off as soon as possible before something happened to them. This 'something' was never specified and remained nameless.

One day Rukumani had a visitor. Boy ran into the house as she was drying her long hair and shouted, 'Ama! Akka's boy friend come.'

Rukuman's mother and grandmother were in the kitchen and both looked horrified.

'You keep quiet, Boy! You too young to know about such things. You go out and play.' Rukumani's mother tried to quell him.

In the meantime, Rukumani had hurriedly dried her hair, coiled it into a temporary bun, and went out in great fear as well as anticipatory pleasure, expecting to see Devanayagam. To her relief and disappointment, it was Johnny Chew.

'Hi, Ruku, you look cute like that', said Johnny. At the same time Rukumani's mother came into the front room. She pretended not to have heard it. Rukumani looked flustered and hastily introduced them. Then she composed herself and asked Baby to go and fetch a drink for her friend. Her mother stayed a bit in the room, examining Johnny's face until Johnny said, 'Don't let me disturb you, Auntie. Please go and carry on. Ruku and myself can sit here and have a chit-chat. Haven't seen each other for a long time, you know.'

Rukumani's mother left with as much dignity as she could muster. Baby came back with a glass of pink syrup and milk which she presented to the cheeky Johnny, who remarked in her presence, 'Cute little thing ah, your sis!' Baby squirmed with shyness, satisfaction and dread, and shuffled out of the room. Fortunately, her mother was already out of earshot.

'So, how you getting on? I feel helluva bored, man. This town is a real sleepy-hollow. I'm going back to the U for some fun. Here too many eyes and mouths. Can't even take my girl friends to pictures without gossipers talking.'

Rukumani had a feeling that Johnny had come to her hoping for a chance to talk about Amy, but she still feared that his talk of girl friends might make her mother think that they were indulging in improper conversation. She therefore brought up problems about classwork and lectures so that, should her mother eavesdrop, she would only hear harmless conversation going on. Johnny, however, was in a dangerous mood, and would not be side-tracked.

'Eh, why you won't talk about your friend ah? You girls all stick together and frus us. If you help me I also can help you with Deva, you know.'

Rukumani went quite cold with fear. She hurriedly told Johnny not to talk about Devanayagam, and for once Johnny caught her mood of urgency and changed the subject. When Rukumani found that Johnny was going back to the university in a couple of days, she thought that he could give a letter from her to Devanayam. There followed a whispered agreement between them that Johnny would come back for the letter the next day, as that was easier than Rukumani's cooking up an excuse to leave the house alone to go and post her letter. Rukumani, meanwhile, said some very encouraging things about the state of Amy's affections for Johnny, and the latter, usually quite full of self-confidence, went away feeling all the more satisfied with himself.

As soon as Johnny had gone out of the front door, Rukumani's mother started.

'Young people nowadays have no shame. My mother would have sent me out of the house if I had entertained a boy friend as freely as that. All that whispering. What will the neighbours think? A Chinese boy coming to whisper with my daughter. Do the Radakrishnans next door allow their daughters to run wild? Do you ever see a strange boy visiting the daughters of Tharmaratnam? But my daughter different. She wants to be modern and be seen with all sorts of men. Why do you want to make me suffer in my old age? Can't you see that I'm trying to arrange a good, respectable marriage for you? Show your gratitude. You're driving me to the grave!'

It was mainly Boy's fault, thought Rukumani. If he had not announced Johnny like that, perhaps her mother would not have got the wrong idea. She half-regretted asking Johnny to deliver her letter, because his reappearance the next day might cause further complications. However, she was in such a state about Devanayagam that she was almost glad that her mother suspected Johnny of being in love with her.

The next morning Johnny called. He stayed for some time because the front room was not quite empty and Rukumani could not pass him the letter, which she had written in the dead of night with many sighs and tears. Even as she sat making conversation, she thought of possible amendments to her letter, but decided that there was no time or opportunity for that. In a fortunate moment when the front room was empty, the letter did change hands and after more hearty conversation, Johnny left.

After some time Rukumani's mother came out from the kitchen. 'Your father will know how shameless you are. Passing love-letters to boy friends.'

Rukumani panicked. They knew about Devanayagam.

'We have been Ceylonese Tamils for a long time. Do you think you can spoil our blood now?'

Saved! They thought it was Johnny. A reprieve, if an awkward one. The sight of a self-satisfied little figure peeping round the door convinced her that Boy had somehow seen her passing the letter to Johnny. She managed to force him to receive her look of pure hate although he tried to avoid looking at her. That evening there was a showdown when her father came home from the office. Both her mother and grandmother had ignored her for the whole day, and Rukumani rejected the friendly advances of Baby, who could not help concealing her relief that it was not she who was under fire. As for Boy, he was treated with lavish affection by the grown-ups, who more or less regarded him as the defender of the honour of their house. He did not dare come within two feet of Rukumani but enjoyed his exalted position at a safe distance from her.

Mr. Sambanthan was silent at first when his wife told him of their daughter's guilt. Then he refused to eat and started to cry. He accused his wife of not teaching her daughter morals. She offered to commit suicide. Boy cried and begged her not to kill herself. Baby shivered with fear in case they started on her as a preventive measure. Mr. Sambanthan's mother, who was silent for a long time, suddenly announced that she would either leave the house and beg, or kill herself if the family were disgraced by Rukumani. At this, Rukumani's mother, not to be outdone, offered afresh to kill herself either by hanging herself or by swallowing poison. As an afterthought, she said she could starve herself after the fashion of Gandhi. Rukumani, after denying that there was anything between Johnny and herself, kept quiet and looked sullenly at the ground. Sometimes she cried tears of vexation, at the same time feeling triumphant that they had not discovered that she was really in love with Devanayagam. When everyone was exhausted with tears and death-threats, it was time for bed. Rukumani heard her parents quarrelling in their room. She heard snatches of conversation and gathered that they were going to make firmer arrangements for her wedding.

When Johnny arrived at the First College, he saw Devanayagam lying on one of the multi-coloured plastic string chairs in front of the dining room.

'Eh, Deva, stop dreaming of your girl friend, man. I visited her in Ipoh lah, but don't be jealous ah, because why? Here is a letter for you.'

Johnny threw Rukumani's letter towards the startled Devanayagam, and several young men who were sitting around in their flip-flops tried to catch it. After a minor skirmish, Devanayagam retrieved the letter and retired to his room to read it.

'Dearest Deva', Rukumani believed that one way of making a man respect you was to be a shade less ardent than he, and this was her answer to Devanayagam's 'Dearest Darling'.

Your ever-loving

Ruku

This he had not communicated to his true love, and his conscience was beginning to make him feel uncomfortable. As he lay on his bed, he felt as if he wanted to be free of all commitments, but at the same time felt too weak either to break off with Rukumani or to disobey his family. The dowry had all been settled between the families, and although he had said to his parents that he did not want to hear anything about it, his mother managed to let him know that he was getting $80,000 as well as a house and a plot of land, in spite of the fact that his bride would be a BA by the time they got married.

The Sambanthans were desperate. If they allowed Rukumani to return to the university for her final term, they were sure that she would do something shameful with that Chinese boy. Already gossips were spreading rumours, and if these rumours reached the ears of the bridegroom's family, they might withdraw their offer, and it would be impossible to marry Rukumani off. On the other hand, if they refused to allow her to finish her degree at the university, their hopes of their daughter becoming a BA would be dashed. Worst of all, the bridegroom's family would demand more dowry if she did not become a BA. Further quarrels ensued between various members of the family, and aunts and uncles came and proffered advice. It was the aunts more than the uncles who had a great deal to say. The uncles usually shook their heads at Rukumani for causing all this pain, and said that such things never happened when they were young. The aunts were more dramatic. They wept often and talked about the death of maidenly modesty and family honour. By this time their husbands had settled down in a little corner to argue about politics in Malaya and India. The aunts cooked meals in-between their bouts of crying, and the person who enjoyed these visits most was Boy, because the aunts petted and over-fed him. He was safe from all accusation of misdemeanour because he was considered too young to know about marriage. Baby, on the contrary, trembled lest she should be included, and she was sometimes the object of a warning such as 'Let all young girls beware and not be fooled into betraying their family name.'

Then the decision was taken. There would be no final term for Rukumani. It was decided that the increase of $20,000 in dowry was worth the risk of family disgrace. When negotiations with the other family were concluded, this was announced to her. Rukumani felt that the time had come for her to disclose her secret. She did so and named Devanayagam as her lover. She thought that the family would relent when they found out that her lover was a Ceylon Tamil after all. To her great surprise, further imprecations were heaped upon her head.

'How dare you choose somebody for yourself? Now you have gone and undone all our work', wept her mother. 'This Devanayagam was the one we had arranged for you. Now that you have been so brazen and shameless as to have spoilt yourself with him, do not expect us to let you marry him. In my youth, we never looked at a man until we were married.'

'Ama, I never did anything wrong with him', protested Rukumani.

'Don't try and tell me shameful things', cried her mother.

Chaos again. The family had to meet delegations from the other side, who were equally shocked that their son had had a secret lover all the time. There were more exclamations about the shameless deception of the modern generation. Devanayagam's father wrote him a very stern letter:

You have this day filled our family with great shame. Your mother and I are heart-broken to hear that you were having an affair with the person whose name I won't mention. This is a judgment of God! She was the one we had chosen for you but fortunately we found out she was unworthy of our house and name. We wanted a bride for you who would earn more respect for our family, but she has been led by her great shame to confess that you were going together at the U. Did you think you would fool us by pretending that you did not know that it was Mr. Sambanthan's daughter who was to marry you? No wonder you were so obedient.

Let me tell you this. Learn hard at the U and after this let it be a lesson to you that you should leave everything concerning marriage to your elders and betters. You are far too young to think of such matters yourself.

Your mothers and sisters are ill with grief.

Your grieving parent,

Pa

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

On a high mountain there was a cave in which lived a strong and powerful lion. Although he was the the king of the beasts, he was not able to stop one of his smallest subjects from annoying him. This was a little mouse. Every day, when the lion had his afternoon nap, the naughty mouse would gnaw the tips of the lion's royal mane. The lion found this very annoying indeed, especially because the mouse always darted into his mouse-hole as soon as the lion woke up fully.

In desperation, the lion coaxed a cat to come and live with him, pampering him with bits of meat from his hunting-trips. The cat was called Curd Ears, and his creamy ears twitched diligently as he watched the mouse-hole. So the mouse kept inside his hole and the lion took his rest undisturbed. Curd Ears grew sleek and fat because whenever the lion heard the mouse squeaking, he gave Curd Ears more and more to eat to make him stay as his mouser. The mouse, meanwhile, could not come out of his hole even to look for food. But one day, the mouse was so hungry he had to come out of his hole. Curd Ears immediately pounced on him and swallowed him up.

After this, the lion no longer heard annoying mouse squeaks from the mouse-hole and so he no longer bothered to feed his retainer. This story shows that a servant should always make his master need him all the time. Otherwise, like the over-diligent Curd Ears, he might lose his job.

10) Written in 1979 for children up to the age of eleven to teach them about Indian culture, from A Handbook of Hinduism for Teachers, pp. 10-11; see Catalogue, no. 7.

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

Once a hunter found a magic bird which produced gold droppings. He carefully set a snare and caught the bird, thinking that his fortune was now made. But when he got the bird home, he became very worried that the rumour that he owned such a priceless bird would reach the ears of the king. If that happened, he knew he would be punished for not giving the bird up to the king. Then, deciding that it was better to remain poor but safe from the king's envy, he went to the king and gave him the bird as a gift. The king was very pleased with this present and asked his guards to keep careful watch over the bird.

However, one of the king's advisers said to the king, 'O king, why do you let this hunter make a fool of you? Who has ever heard of a bird with gold droppings? Your Majesty should show him what you think of his incredible story by setting the bird free.' The king thought this was very wise and he set the bird free. The bird flew upwards, perched pertly on the lofty archway of the door, and neatly aimed some gold droppings right in front of the king and his counsellor. Then he mocked them by reciting in Sanskrit:

I was the first fool because I was caught;

The hunter was the next fool, for now he has naught;

The king the third fool, for he was taught

By the fourth fool to lose what can't be bought;

We are a circle of fools as round as a nought.

A HANDBOOK OF HINDUISM FOR TEACHERS

Sarasvati © Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

Nandi © Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

Krishna © Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

12) A story written in June 1980; published in Southeast Asian Review of English, vol. 2, August 1981, Department of English, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, pp. 40-3. Corrections of some minor printing and other errors in the published version have been incorporated here.

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

When I left this village, I didn't dare think of the day when I would be back again. Then my little boy was crying. Perhaps he was hungry, or perhaps it was because his mother was leaving him with a strange pig-farmer's wife. I'll never know why. Now I didn't want to think of the little girl I had left the night before. I had patted her to sleep and she had held on to my thumb in her usual way, so that I wouldn't be able to go away without waking her up. I hoped my aunt wouldn't tell her that I had forgotten all about her. My aunt sometimes had a sharp tongue, although she was a kind woman, and would sometimes say things she didn't mean, often just to tease a child.

That aunt had met me at the Ampang Street bus station, four or five years ago now, when my ears were still full of my baby's cries. She told me how lucky I was. Nobody would've agreed to employ somebody like me if I hadn't been the relation of an old and trusted servant. I was to remember this and was not to behave like a fool again. I knew she was right and remained silent, and this pleased my aunt. She liked others to keep quiet while she talked. 'Behave yourself, do your duty, and nobody will be unkind to you.' I had done what I was told and found that she had spoken the truth.

I approached the little house and could smell the pigs. There were a few children running around in their bare feet and they crowded round me, staring at me. One of the oldest ran to find his mother, the woman I was looking for. I tried to pick out my son, but none of them looked like him. They were all dark-skinned and dirty. Then I saw the woman coming round from her vegetable patch at the back of the house. We knew each other straightaway although we had both changed, each in her own way. She'd had more children since, I could see that. She motioned the way to her house, and I followed her, neither of us saying a word. Like me, she had never been one for words, I remember, and that had been one reason why I'd placed my boy with her. I'm sure my aunt would not have recommended her if she had been talkative. Her husband was still feeding the pigs and would not be in till long after I had gone away with my son.

She made a cup of ovaltine for me and put it on the oil-cloth on the table. I pulled out a stool from under the table and sat down while she sat in a chair opposite me. An older girl unfastened a baby from her back and brought it to her mother, who started feeding it. Then I saw my son. He was rough-featured, but, like my pretty little girl, fair-skinned. He was mine. I too am fair-skinned. That is my one beauty. What would he think, I wondered, if I showed him the toys that I had brought with me? But not here, not in front of the others. I noticed that this woman had many sons. The gods are strange in granting their favours. To those like ourselves, they often send sons. I thought of my pretty mistress and her longing to have a son. Had it been my fault?

She was a helpless little thing, my mistress, and should've had her baby before I arrived, according to my aunt's calculations. My aunt had nursed her from babyhood and handled her easily. Even the master was a bit afraid of my aunt. It was my aunt's idea that I should go to the temple to make daily offerings to Goon Yam, the Goddess of Mercy, so that the mistress would have a baby boy and recover quickly. I knew my aunt had worked out in her own way that the baby would be a boy, and since she knew that she would be looking after the mistress herself and that there would be no danger, this was her way of ensuring that I would be accepted by the other servants when the Goddess granted those favours to the family. I was glad to do whatever I could to please my aunt and the family, though I wondered at my aunt, sending somebody as unworthy as myself to make offerings for such important favours. As I watched the incense papers curling up in the low pagoda-shaped open furnace in the courtyard of the temple, I counted the years that would separate me from my own baby. Was it my fault that our mistress had a girl instead? It was a beautiful baby, but it was not a boy. My mistress wept, but she said I had done my duty and she would not blame me. My aunt was furious with me. I was a good-for-nothing, and would probably be sent packing, as I deserved to be. But the other half of my prayers had been answered, for the young mistress recovered in a few weeks' time, with my aunt's nursing, and my crime was overlooked even by my aunt, who bustled around the mistress, whipping up almost as much adverse wind around her as she succeeded in keeping out with blankets and wraps. I was sorry for the mistress, but I was glad to become the wet-nurse of a little girl instead of a little boy, who would've reminded me too much of my own baby. She was given to me to suckle within a week of my arrival. Then after she stopped needing a wet-nurse, I was kept on as her nurse. I didn't know then what years of looking after her would do to me. Still, nobody can love another child better than their own.

My ovaltine was getting cold. The woman was saying something to me. She wasn't being inhospitable, but she wanted me to leave as soon as I could, so that we could both get it over with. She knew I had come to take her boy, my boy, away with me. He was holding the little baby's thumb while it sucked at his mother's breast. In a few minutes, he would be reunited with me, away from all this, and we would be able to start our new life together. He would not have to share what little I could give him with all these dirty little children. He would be better off. My mistress had given me enough to start a little stall of my own, and I had saved enough to send him to school one day. He would be able to help me at my stall after school. One day he would be able to see for himself that I was only taking him away for his own good. Now it might be a little painful, but children always forget. Then one of the younger ones fell down and started crying. My son ran to him and said, 'Here, come to your big brother.' The little toddler stretched up his arms to my son, and my son lifted him up clumsily, patting him to calm him down. 'It's all right', I said to the woman, 'I'm going away now, and I'll keep sending you some money every month.' She didn't say a word, but went on feeding her baby while I walked away from the smell of her home and her village.

I have now given up the idea of starting my own stall. A friend of my aunt's has found me a job in a place that makes paper things for offering to the dead, next door to a coffin shop, in a little town miles away from my little girl. I earn enough to send some money every month to my aunt, over and above all my other expenses. My young mistress would always welcome me back, but I'm not going back there again either. And nothing will ever induce me to marry and have more children.

Her hair was different. One of my earliest memories was watching her do up her hair. She used to have hair down to her waist, and every morning, while I lay on our bed, after she'd got up, I would watch her combing her hair with an old bone comb. She always sat on the floor in front of the window, with one leg stretched out. She had a complicated way of holding one end of her long black hair between the big toe and the second toe of the stretched-out foot, while she combed and plaited the taut hair into a thick rope. She then tied it up neatly with a short length of red silk thread, and packed her comb and pins away in a small tin which she put together with her clothes. By then the room smelt of her hair oil. Next she would come to our bed to wash and dress me, and I would put up my arms to be lifted up and crooned to. I thought her repeated 'oy oy, oy oy' as she rocked me the most musical sounds in the whole world. Now her short hair was permed rather frizzily, and she looked quite strange. She didn't look like Mama and her friends, who also had permed hair. They somehow looked right with their permed hair, playing mahjong, but Gau Chieh looked odd with her permed hair. I suppose it was partly because I had never seen Mama and her friends with a single plait down their backs before. Nor could I ever imagine it.

Gau Chieh had also changed her black trousers and blue jacket for an ordinary samfu, and this made me almost too shy to look at her. I wondered if she even used make-up these days. I used to be able to jump up and down on her without her ever saying 'don't'. Maybe black didn't show the dirt? I wondered if her sons were allowed to jump up and down on her lap. Of course I wouldn't have done the same thing on Mama's lap, so maybe they didn't either.

I wondered if she still went to the temple to burn incense papers. One of the things that I had enjoyed most was being taken to the temple where she had to make all sorts of offerings on Mama's behalf. Against one of the outside walls of the temple was a golden-green coconut tree, and the late afternoon sun filtered more gold through those leaves, to blaze against the white-washed wall. I would hold on to Gau Chieh's hand and jump up and down with joy at nothing in particular. It was enough to be together. There was a beautiful gold-fish pond in the courtyard, with steps leading down to a stone edging round the pond, surrounded by a pretty walk. I used to be allowed to sit on the edge of the pond watching the gold-fish swimming round and round while Gau Chieh bought whatever she needed from the woman who sat behind the counter at the entrance of the temple. I couldn't fall in as there was a piece of wire netting covering the pond. On feast days I was given pink and purple rice cakes, which I shared with the fish when no one was looking, dropping bits of cake in between the meshes of the netting. Then she would call me, and I would go round the whole temple with her while she put joss-sticks into large shining urns and poured oil into a small red lamp high up in a tiny niche in a dark corner of the temple. Sometimes I had to kneel on a small cushion for a while. I felt hungry then because I could smell the roast chicken and roast pork that people had brought and placed before the gods, and those smells were all mixed in with the incense and joss-sticks. In after-years, when I thought of Gau Chieh, those smells used to come back, together with the smell of her particular brand of hair oil.

But the climax of our visit to the temple was when she lit a cunningly-arranged pile of incense papers with a burning joss-stick placed near the entrance of the temple. I had to keep out of the way at this point. Then she would carry it deftly, the flames getting bigger and fiercer every passing moment, towards the open furnace, which was shaped like a pagoda. Once it was safely in, she would let me run to her, hold her hand, and watch the flames rising higher and higher as they crept round each layer of incense paper. 'Can you count?' she used to say. 'See if you can tell me how many layers of paper are left.' After she left us, I sometimes went with Poh Poh to the temple, but I would wander off to the gold-fish pond whenever it was time for her to feed the incense papers into that furnace. I couldn't bear to watch the incense papers burning.

It was a rather boring visit, and I felt embarrassed about not feeling more enthusiastic about Gau Chieh and her children. Gau Chieh asked me how I was doing at school and how my parents were. Poh Poh talked about all sorts of things while we listened. Now and then, when one of the boys started making a noise to attract her attention, Gau Chieh absent-mindedly reached out to smack him. I wonder now if I had really missed her that morning when I woke up and found that she wasn't sitting in front of the window combing her hair, although I thought the smell of hair oil was there in the room. That was another thing. She no longer smelt of hair oil. Perhaps hair oil didn't go with permed hair. I remember I had looked for her tin with her hair things in it when they told me she'd gone home to look after her nephew. Home? I'd always thought her home was with us. But when I found that the tin was gone, I knew that even Poh Poh wasn't merely teasing me. That day Mama let me build towers with her chips during mahjong, something I wasn't normally allowed to do because it brought bad luck on the player. I pretended to enjoy myself just to please Mama.

And now Gau Chieh had moved again, into another home with her husband and family. Her husband was not there. He made coffins in Gopeng. Poh Poh had pointed out the shop to me in a side street as our taxi went up the High Street in Gopeng. I could just make out the relentless shapes of two carved coffins casually sticking out on to the pavement on the shopfront, surrounded by wood-shavings, as we passed that street. So I didn't see Gau Chieh's husband. I was quite glad not to as I wasn't sure whether to call him Lau Goh or Lau Sook. Should he be regarded as a kind of brother or as a kind of uncle? However, I'd never held anything against him since I'd always known that he hadn't been the cause of Gau Chieh's sudden disappearance.

And now I was very glad I wasn't going to live with Gau Chieh in Tambun. It was a relief when Poh Poh rose to go at last. It sounded absurd, but somehow not unexpected, when Gau Chieh said to Poh Poh as we were all standing up, 'She's much taller than when I last saw her.' On the way back to Ipoh, I knew that Poh Poh would point out the coffin shop again. I looked out automatically and saw the same two coffins, now seen from another angle, still surrounded by the wood-shavings. I idly wondered how those shavings would look if they were burning in that open furnace. Would they also layer as they burnt?

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web Page

Last update on 18 May 2003.