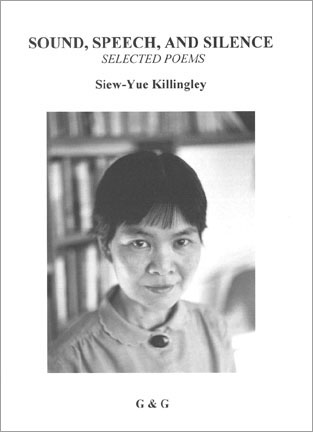

Siew-Yue Killingley (née Leong) was born in Kuala Lumpur on 17th December 1940. She was educated at St. Mary's Girls' School (1947-57), where she was Captain of McNeil House and School Captain, the Victoria Institution (1958-59) and the University of Malaya. She graduated with honours in English in 1963 and then studied for an MA in Linguistics, awarded in 1966. She went on to study linguistics and phonetics at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, where she was a Forlong Scholar. In 1972 she was awarded a PhD for her work on Cantonese grammar. She has taught in schools in Malaysia (St. Mary's Girls' School and St. John's Institution in Kuala Lumpur; Methodist Girls' School in Klang; La Salle Boys' School in Petaling Jaya), at the University of Malaya, in various departments at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, and at Newcastle College (formerly College of Arts and Technology). She taught for nine years at St. Mary's College of Education, where she was Senior Lecturer in English, until she was made redundant when the college was closing down. This led her to found Grevatt & Grevatt in 1981. Since 1987 she has worked in the Centre for Lifelong Learning (formerly the Centre for Continuing Education) at the University of Newcastle, where she teaches linguistics and Chinese (Mandarin).

Flute imagery and technique are important motifs in her poetry. Inspired in childhood by an uncle who played the Chinese flute naturally, she became a dedicated student of the flute. She began studying the flute with Mahmuddin bin Ngah in Kuala Lumpur and continues to study it in Newcastle while playing in amateur groups.

Siew-Yue Killingley's book publications include the following: Song-pageant from Christmas to Easter, with Two Settings (with Percy Lovell); The Pottery Ring: A Fairy-tale for the Young and Old; In Sundry Places: Views of Durham Cathedral (awarded Second Prize in 1982 in a competition to mark the Ninth Centenary of Durham Cathedral); Where No Poppies Blow: Poems of War and Conflict; Lent and Easter Cycle: Poems for Meditation; Northumbrian Passion Play (performed to full houses in Newcastle in April 1999); Other Edens: Poems of Love and Conflict; English in Education: How the Linguist Can Help; Cantonese Classifiers: Syntax and Semantics; A New Look at Cantonese Tones: Five or Six?; Cantonese: Languages of the World/Materials 06; A Handbook of Hinduism for Teachers (with Dermot Killingley, Vivien Nowicki, Hari Shukla, and David Simmonds); Sanskrit: Languages of the World/Materials 18 (with Dermot Killingley); Learning to Read Pinyin Romanization and Its Equivalent in Wade-Giles: A Practical Course for Students of Chinese. She is a co-reviser of vols. 1 and 2 of Beginning Sanskrit: A Practical Course Based on Graded Reading and Exercises by Dermot Killingley (vol. 3 forthcoming).

Her published essays include the following: 'Lexical, semantic and grammatical patterning in Dylan Thomas (Collected Poems 1934-1952)'; 'Semantic opposition and equivalence in "The Wreck of the Deutschland"'; 'Peter Brook's film The Mahabharata: Hybrid language, race and culture in narrative discourse'; 'Time, action, incarnation: Shades of the Bhagavad-Gita in the poetry of T. S. Eliot'.

Only a small sample of Siew-Yue Killingley's diverse literary works can be presented in these Archives. It is in two parts. Further details of her works displayed here are listed in a catalogue at the end of this text.

Siew-Yue Killingley, the author of the excerpts below, hereby asserts and gives notice of her moral rights of paternity and integrity under sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of these excerpts taken from her unpublished and published works.

All rights reserved. No part of these excerpts may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the copyright holder, c/o Grevatt & Grevatt (see address in the catalogue below). Preliminary enquiries may be made via Chung Chee Min, to whom permission was granted on 16th March 2000 to reproduce these excerpts for the Victoria Institution Home Page.

POETRY AND DRAMA IN VERSE AND PROSE

1) Excerpt from Song-Pageant from Christmas to Easter, with Two Settings, p. 12. Published by Percy Lovell, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1981.

The garment © Siew-Yue Killingley 1977

In Brickfields, in his blind hovel

Crouches Ah Wong by owl-light,

Bonily sewing for ample frames

Cheongsams to gladden the sight

Of shining soft brocade.

Some poor man made a garment,

Not of rich brocade.

It grew mockingly kingly

And wrapped your pain-wracked frame

Until stripped off as dressing,

It undressed your unbroken bones.

Ah Wong's bones are your very bones;

His lean sufferings are your own

Garment, flesh stripped bare to the bone.

2) Excerpt from In Sundry Places, p. 5; see Catalogue, no. 2.

Remembrance Sunday

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1977

I am too young and unscathed to fully remember

The grim meaning of Remembrance Sunday.

But for many this pretty poppy will never

Be a mere symbol of a happy summer's day.

For many have suffered who now sharpen their memory

On the black whetstone of past hate and fear

Stocked in their lifetime with the armoury

Of war, to be trotted out for inspection each year.

Still, I am not too young to sometimes remember

The meaning of love's daily trial and dying.

And this red emblem worn so bravely forever

Recalls for me the death of mankind, lying

For centuries on our hands, a red reminder

Of the blood we spill daily from a true nature

Flush in the wine but drained in the blanched wafer

Donated to us to help us bravely remember

To emulate the warrior whose soul fought his body,

Cringing in human fear from the enveloping sea

Of pain as he offered up his own blood and body,

Saying, 'Do this in remembrance of me.'

3) Excerpts from Where No Poppies Blow, pp. 54, 53, 16; see Catalogue, no. 1.

Recall the last trumpet

© Siew-Yue Killingley 1980

In a white darkness of dawn,

A bland sun bathes the wounds

Of a star-shattered world.

And an erstwhile Sunday red

With the sunny poppy of the dead

Of two world wars is blacked out

Of experience. Not one dismembered

Member of dishonoured mankind

Is buttonholed to trumpet the bland

Blasphemy of man's sleight of hand

In remembering the fast dead members

Of a past living world of wars.

Achieve the impossible,

And remember the future

(A new Hiroshima)

Where no poppies blow.

CND march © Siew-Yue Killingley 1981

In Flanders fields the poppies blew;

We march in memory, two by two,

And mark our place. In time the sky

Will shroud no birds; no vultures fly

Above the quaintly dead below,

Rosy in man-made sunset glow,

All love reduced to fiction's lie,

More cunningly complete than Flanders fields.

In Flanders fields, if we had died,

The living poppies would prove we'd tried

To mark our place as men of peace.

But in the future, life's release

Will not be marked by grave or flower.

And silent minutes will have no power

To sound the last post for peace,

More hollow than the lie of Flanders fields.

Fragments © Siew-Yue Killingley 1983

Rhythmic chanting

Of that glib syllabary:

ka, ki, ku, ke, ko,

sa, si, su, se, so.

Hypnotic, soporific,

Mystical, poetic.

Then dinner time,

And another attack.

But this time,

While sirens shrieked

And the world splintered

Like glass, we squatted

Or sat under our large

Dinner table. My dinner

Shook in my tin plate

With a pretty red border,

And jerked out like syllables

Of grain on the floor.

Eyes reproved,

Speech being useless.

Discouraged or frightened,

I let my plate crash

Food-downwards on to concrete

With a louder percussion

Than any explosion

Of those obtrusive

Japanese-British gifts

Falling about our ears

To the poetic cadence of non-speech:

ka, ki, ku, ke, ko,

sa, si, su, se, so,

a, b, c, d, e.

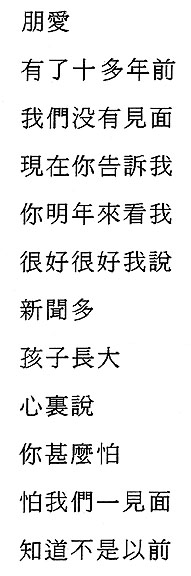

4) Excerpts from Sound, Speech, and Silence, pp. 17, 14, 9, 3, 19, 69, 25, 63, 10; see Catalogue, no. 3.

Peng Ai © Siew-Yue Killingley 1976

Transliteration¹

Peng ai © Siew-Yue Killingley 1976

Youle shi duo nian qian

Women meiyou jianmian

Xianzai ni gaosu wo

Ni ming nian lai kan wo

Hen hao hen hao wo shuo

Xinwen duo

Haizi zhangda

Xinli shuo

Ni shenme pa

Pa women yi jianmian

Zhidao bushi yiqian

Line by line translation

Friendship © Siew-Yue Killingley 1976

More than ten years have passed

Since we last met.

Now you tell me

That next year you're coming to see me.

'Wonderful', I say.

There'll be lots of news.

The children are growing up.

In my heart I ask,

'What are you afraid of?'

I'm afraid that as soon as we meet

We'll know that now is not then.

1. In the four Chinese poems in the book [Sound, Speech, and Silence], the character text is accompanied in each case by a transliteration in Mandarin using Pinyin romanization, omitting tone marks. This is followed by the English translation

When my love is quietly sleeping,

All the living years become

A human train of time-traps

Caught in the frail crook of my arm.

I wind my numbing arm to cloak

My love, to shield that human head.

And see the end of living fears,

Asleep in the tunnel of the dead.

But time's trap will snap this human frame

And crack my cold arm with lead.

And bind my life across those rails,

Caught stiff by the tyranny of the dead.

Weighing the past © Siew-Yue Killingley 1987

Now what did she think of

The length of each long day

And repeated lengths of night?

She did not speak much

But to order in quiet tones

The required meals of the day;

Or, if it could be called speech,

To murmur some syllables to the dead

While sticking pungent incense

In the jar outside her door.

(For silence in a woman or wife

Was much prized by the Chinese.)

When she did speak, it was Cantonese.

Did she use it then when praying

To her Hakka-speaking husband -

Long-dead before I was born -

Morning and evening at incense-time?

Yes, she was chained to the past,

But also ordered the present

To the end that new happenings

Would be linked to that past.

How else could she endure

Our indifference to incense,

Polite boredom with stories

Of a world all unknown,

Of dead Grandfather's exploits

In healing and in learning?

Her parcel of the past

She tied up in her present.

And so she measured in steps

The length of her sitting-room

In her silence of incense,

In near-silence of days

And the silence of nights,

Weighing thoughts of her past

In blank scales of the present.

The Mourners: Maundy Thursday © Siew-Yue Killingley 1988

One had lost her son in the war;

Another had some unspeakable sorrow;

Others clasped friends in fixed poses

Of pain forever frozen in my brain.

Some were dead and should be decently covered,

But were resurrected for the world to view.

Speechless, frozen, these stills are stolen

From subjects whose griefs once had meaning

Now erased in these bland tokens of betrayal.

A Kiss © Siew-Yue Killingley 1989

They asked me bashfully, 'Is it sinful to kiss?'

How could I possibly ever answer this?

We were all young together, though I

To them was old at twenty-five - and wise,

They thought, or else they wouldn't have asked me.

How complex it was to consider a kiss.

Their up-turned faces wanted plain certainties:

Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, non-Catholics, atheists

Receiving 'Moral Instruction'; they were eighteen,

So above all they wanted my answer to this.

'It partly depends on whether you enjoy it',

I tentatively began, 'and whether the other person

Wants it.' Some boys beamed at this, but one

Serious girl reproved me for levity, for this

Was 'Moral Instruction': surely it was sinful to kiss?

Why had I thought I could teach these young hearts,

Eager for one answer to a question so complex?

I envied the Brothers taking Catholic pupils

Elsewhere through their catechism, so cut and dried,

Brothers Celestine, Cornelius, Damian, so true and tried.

Here we were all young, and had our narrow vision

Fixed on just one aspect of a wide teasing genre.

Unknowingly I might have given them the right answer,

Though none of us knew exactly what we were about,

And didn't consider complications that are plain to me now.

Did Judas enjoy that kiss, which Christ received with pain?

Does such kissing make the kisser wish to kiss again?

At baptism does the priest enjoy kissing bald heads

Of infants; and do those babies want to be kissed?

Do we assure ourselves and others by persistent kissing

On greeting and leave-taking that all is well

Though all that remains between us is hardness of shell

Glossing relationships that once didn't depend on kissing

To replace the essence of all that is now missing?

Now I have learnt, too late to impart to them,

Not to give pain by refusing to receive kisses

Of habit, both public and private; but I'll not kiss

Unless I wish to impart, and another to receive, pure bliss.

If 'sin' must come in, let it rest in insincerity.

Tiananmen, June 1989 © Siew-Yue Killingley 1989

Old men should not beget

More children lest they forget

Their mortality and invest

Their last throw for wisdom

In a last show of virility.

But these old men have begotten

Death on children, their youth forgotten:

Such immortality's like incest;

Their last throe of folly

Is their last word to manhood.

Old men have pressed to earth

Youth's bloom and sap at birth,

And choked its trusting cries

And crushed young minds with lies

Of love in a crunch of tanks.

When the blinding folly of old men

Makes them frantic for the death of heirs,

Tian has no eyes, an is dead in Tiananmen,

And hope blinks at its last grey hairs.

Petaling Jaya © Siew-Yue Killingley 1990

A drop of sound in the dusk

Of dawn, the muezzin's call

Moans faintly through loudspeakers

To the lonely accompaniment of cockcrow.

Both swell the air with echoes

Of pure sound for a brief bar

Before the fierce day descends

In a hot prison of noise and cars.

Flute and Strings © Siew-Yue Killingley 1994

Awake, my flute, and struggle for a part

With all your art.

The cross taught all wood their strings

His suffering rings;

And taught what key to play the theme

Of lament, to lose, to rise, redeem.

It is written wood alone can speak

And reach that peak

Where their taut strings twist a song

Three days long

To suffer their strings to sound discords

In likeness of taut arms nailed to boards.

But though the sleeping flute can only play

With slow delay

When warmed and wakened to sound and sing

With throated ring,

It can be taught to speak in highest speech

The deepest laments that speech can teach.

As from the tree a pinned bird's call

Can touch more quickly than its later fall,

His throat, a cold flute, in final call

Sings unlike strings, but sings his all.

Chinese New Year Cards © Siew-Yue Killingley 1995

The New Year cards started coming in

From the tropics with greetings of abundance

In spring, accompanied by foot and mouth-

Drawn pictures of old men and gold-fish

Signifying longevity and teeming wealth.

I reciprocate with cards from Great Wall

Supermarket to my relations in the tropics

Wishing them the same, cards framed

In oriental blossom of red Chinese plum,

Auspiciously blushing at their quaint orientalism

In their English setting in Percy Street;

And I remember the yearly elaborate meals

And how I was bewildered that we celebrated

The passing of the winter solstice

With abundance of winter roots

And other Chinese dainties

In the very middle of a hot

And blinding Malayan day.

5) Excerpts from Lent and Easter Cycle, pp. 6, 8, 10, 15, 22; see Catalogue, no. 4.

Day 11: Orpheus in the Underworld: Overturning Psalm 58 © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

Once again a polarization of good and evil,

Guilt and innocence in an overturned judgment

Of a murder buried in most people's minds

But embedded still in the family's snake-bite,

Clutching at the shades of their utter loss.

This chant sounds like a turbulent movement,

A throbbing judgment even from the first

Opening chords jabbing high notes which try

Both singer and listener, pushed along

By the press of its sustaining accompaniment,

Straining to achieve its elusive melody,

Plucking a discordant alpha to keep in tune.

Day 16: Tiananmen revisited © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

Hidden from public view in some grey mausoleum

Of the imagination, he suddenly flowered

Grimly in colour on screens and in photographs,

The centrepiece of a clearly orchestrated

Funeral overture to an enigmatic future -

This stern old master of total control

Who'd composed and executed with consummate skill

The massacre of youthful voices in full bloom.

And as elderly men weep for camera's sake,

A young child sees, and does the same.

Day 22: Still-life from Eden © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

Hand in hand they left that still greenness

Of Eden lost behind them, remembered only

In bright depictions in dim art galleries

Or in the sobering books of Paradise Lost

Framing the vanished beauty of their love.

By the willows of their dried-up Babylon,

Tongue-tied and sewn-up in strange fig-leaves,

Harping a refrain on their vanished garden,

They sat and listened to Haydn's Creation

And wept at the textured replay of their loss.

Day 31: A Chinese folk-song © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

From another North East, in Jiangsu province,

Out of its time and setting, her low voice

Sang warm notes through my silver flute;

Showed her watching for her long-lost love

Sent far from her to the looming tyranny

Of the man-swallowing lengths of the Great Wall.

Her music mourns each passing month,

Even in this transcription for my Western flute,

With notes from nothing set in black and white.

Her lament swells with tiny off-beat notes

Gracing the looming distance from her love,

Marking her time with timeless truth.

Easter Monday: The Easter garden © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

How to present the dark handling

Of human minds and hearts

Throughout time's Lenten season

To the final trumpet of Easter

In a miniature paradigm of Eden

For the children to enter lightly

Into the sufferings of their Lord?

So we made them this pretty garden.

Some admired the spring flowers

And some the purple heather,

Peering into the tiny sepulchre

And fingering lightly the ring

Of thorns on the empty cross.

They saw and they believed

That in some funny grown-up way

Easter eggs came out from that garden.

6) An excerpt from Northumbrian Passion Play, p. 29 (Mary's lament); see Catalogue, no. 5.

Mary's lament in Act 3, Scene 2: Gethsemane © Siew-Yue Killingley 1997

Mary, picked out by a spotlight, enters from the opposite direction. She mimes holding the infant Jesus.

Lay your infant head, my love,

For a time and season on my arm.

Let's pose, in paintings like this, my dove,

Before you fly from me to harm.

Do not allay your heavy sorrows

By sleeping on this stony ground,

For the rock will weep when the cock crows

And your love with thorns is crowned.

I cannot lay your drooping head

Against my arm or heart or breast.

My child no longer, I'll sing instead

A dirge to lay you to your rest.

7) Excerpts from Other Edens: Poems of Love and Conflict, pp. 17, 32, 35, 37; see Catalogue, no. 6.

The Wedding Couple © Siew-Yue Killingley 2000

Created as a new-born pair of creatures

Made the one wholly for the other,

They pose in their quaint wedding finery

For the strange joy of united families,

All enmities both great or small

On their part quite invisible to view

And only sensed in the veiled remark

Oddly strewn among the glowing flowers

That seat placements could've been better

Managed. But they, this shining pair,

Walk in the light of their own fire,

Certain that they will never lie down

On a bed of sorrowful lies and estrangement.

They will never wax old as a garment

And neither moth nor hate nor death

Shall ever in time swallow them up.

The Emmaus Road © Siew-Yue Killingley 2000

Endlessly talking round the disaster

Now gripping Kosovo, they journeyed onward

And mourned the death of peace

Which the enemy had blindly unleashed,

And, heads down to their road of destruction,

Talked of "taking the gloves off"

To deal yet more futile blows for peace.

Thus absorbed, they looked ever inwards

Into the fast-darkening tunnels of war,

So that even when Christ met them halfway

At the death of day, holding up clearly

The refugees' broken hearts as bread

To pull them back into his story,

They brushed him off lightly

As yet another irrelevant casualty

Of what was after all a just war.

Afternoon © Siew-Yue Killingley 2000

In retrospect, we look back coldly on the river

Of events flowing ineluctably from our actions.

In Kosovo, euphoria at Nato's 'sure-win' victories

Feeding the tide of popular caring for refugees.

But now, in the deepening dusk of the sixth hour,

That tide is turning: As women threaten to wash

Our windscreens with tears, babies burdened on their backs,

We suspect they've sold our sympathy down the river.

Dawn © Siew-Yue Killingley 2000 Ode to the Victoria Institution

We sift through rivers of newsprint for some dim reality,

Still veiled like the Tyne in the first greyness of dawn.

How puny our progress in this past week of watching,

Calling on a dying Christ to stem the tide

Of hate in Zimbabwe, renewing our baptisms in the stream

Of dying orphans, intoning "Somalia, Ethiopia",

Beguiling sounds unreflected in the blank old eyes

Of near-skeletons blind to Easter treats.

on Intimations of Mortality from Recollections of Youth

Green playing fields seemed to me

To be cloaked in an all-excluding light,

Surrounding my dim candle wits like a bell-jar.

With my St. Mary s eyes, I timidly peered about,

Gingerly feeling those invisible walls

With my novice hands, like a nun out of convent

Telling her beads with a rosary of tears.

For at St. Mary's, a bright bunsen burner

That lit and worked was an event for joy.

Now I admired and dreaded equally the delicate

Mystery of the chemical balance which the adept

Turned with such cunning art and sophistication,

But which in my timid untutored hands, trembled

Uncertainly, its dainty beam crashing to the echo

Of the sarcastic physics master's loud bellow.

But then I savoured the joy of biology classes,

Where the barmaidish mistress had a large heart

That softened her sometimes severe rebukes,

Rivetting our minds with the mysteries of her science.

At the Sungei Buloh Leper Colony, where the grim marriage

Of deformity to blindness made me weep

At my own sight, and our common mortality,

She surprised me with no rebukes, just a hug.

A more carefree school trip was to the fisheries in Malacca—

A pre-dawn journey by third-class rail,

Then sleeping on hard conjoined desks were treats

That only youth and spontaneous friendships understood.

Botanical drawings honed my poetic craft;

Formaldehyde-steeped dissections showed me mortality.

On hot afternoons we retreated to the border

Of trees round the vast playing fields,

And there I escaped from my fears of failure

As we collected leaves and fruit for botany.

What magic and poetry I found in their shapes

And their botanical names, as I flew with wings

On the wind with the delicately-winged angsana,

A respite from knowledge of certain failure

In physics-with-chemistry, of which I knew nothing,

Though fascinated with the symmetry of molecular structure.

I was charmed by the tall ever-yielding trees,

And completely drawn into the dark quiet womb

Of the library, where I was no longer a stranger,

Remembering my earlier VI days

Of French classes, where learning was like play.

Then I wondered how to lift the heavy bell-jar

Surrounding me as I fought for air to survive

In the drowning atmosphere of my vast ignorance.

Then by some miracle of schooling, the inspired insight

Of various masters, coupled with capricious fate,

Contrived to lift me suddenly out of my prison.

With delicate tact, the chemistry master

Showed some of us our sure suicide course ,

And I entered the new world of the arts stream,

Where the kindness and learning of yet other teachers

Guided me with welcome into a familiar haven

Where learning was once more like play again.

History was no longer the Commonwealth, but China, India,

And even South-East Asia, where I actually lived!

English was just doing more what came naturally,

And even Economics and Principles of Government made sense

When taught by Mr. Doraisamy, so gentle, polite and tolerant.

There was time left over for frivolities like concerts—

The candle-dance, songs—and amateur dramatics.

I was no longer a gasping fish out of water,

Nor a parched oyster out of its gaping shell.

So thank you, you solid and sturdy Victoria Institution.

I never came near to fulfilling your colonial promise.

I never played rugby or cricket for you—

I tried hurdles, but was never in any danger

As I hurtled past, knocking some to the ground,

Of winning a prize that would have baffled me,

Since at St. Mary s we only won abstract points

For the House, and pinned our reusable bright ribbons

Proudly on House banners on annual sports days.

Not for me to shine in inter-school debates

While throwing out casually a learned phrase or two

Gleaned from an obscure copy of Hansard, and thus

Winning cups and shields for the glory of the school.

I never shone like those whose illustrious names

Adorn your book, gleaming like a distant galaxy.

Nevertheless, you harboured potential failures like me,

Allowing us to watch in wonder from the sidelines,

Growing up in our own makeshift way, mindful of mortality.

Copyright Siew-Yue Killingley

15th July 2002

[

Part II - The Short Stories of Siew-Yue Killingley ]

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 17 July 2003.