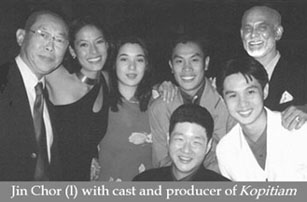

Tan Jin Chor was a pupil of the Methodist Boys School, K.L. from 1946 to 1956 and transferred to the V.I. to continue his Sixth Form education in 1957 to 1958. Despite his short stay at the School, he was both Co-Editor of the Seladang and Secretary to the Victorian in 1957 and 1958, the Assistant Secretary to the Senior Literary and Debating Society in 1957, and represented the V.I. in debating. He acted as Tobit in the 1958 Society of Drama production Tobias and the Angel. The following year, he assisted in the production of Lady Precious Stream. He was also Secretary to Loke Yew House in 1958.

After finishing his H.S.C., Jin Chor joined the University of Malaya to read history. There, continuing with his passion for drama, he directed his old classmate, Krishen Jit, in Oedipus and Antigone while Krishen Jit reciprocated by directing him in The Romantics. In the process these two Old Victorians co-founded the Literary and Dramatic Society (LIDRA) of the University of Malaya. On graduation Jin Chor did a stint at Radio Malaya, and then proceeded to Lincoln's Inn. On his return, he practised law.

Jin Chor's literary bent was already obvious even in his school days, when he contributed prolifically to the Seladang and the Victorian. He has had many short stories published in commercial magazines, poems published in The Malay Mail and other publications. He has also produced radio plays over Radio Malaya. His love affair with the theatre began even earlier, when he, as a tiny tot, played Joseph in a Christmas pantomime in 1946. He has taken part in many Shakespearean and other plays. His last stage appearance was in a minor role in The Odd Couple, staged at the DBKL Auditorium in the 1990s.

His current passion is playing competitive Scrabble and his current Malaysian ranking is thirteenth place with 1587 points. He won the YMCA Open Scrabble Championship in 1996. His other interest is playing golf.

Following are Jin Chor's output while he was at the V.I.: two short stories published (in installments) in the Seladang and poems published in the Victorian:

THE VOICE

"How - how is he, Doctor?" Annie sounded anxious. Poor Annie. I wanted to say something - anything - to assure her. But I did not... because I could not.

As if from a distance, I heard the doctor reply quietly, but not without sympathy.

"I'm sorry, Mrs. Ying.... " His voice trailed off, and for a moment there was silence. I waited but could hear nothing.

They must have left the room. Everything was still and quiet. It was so quiet that I lay with bated breath fearing to break the magic of the moment. But I knew that it was hopeless. I knew that the moment would not last.

And it did not.

With its usual quietness and stillness of tone, the now familiar voice broke into my thoughts and began to speak with beatific joy and transcendent beauty. And I was, as always, held in thrall.

* * * * *

I first heard the story of Grandfather Po-Chueh's death when, soon after we were married, I took Annie to visit my Grandmother, who had fallen ill. Grandmother was living with my sister who was happily married and had two young children, a baby girl and a little boy.

My brother-in-law had gone on a business trip when Annie and I arrived and it was my sister who received us and warmly made us welcome. She was overjoyed at seeing us. Annie at first was diffident (the sweet young thing). But my sister's warmth and kindness soon made her at home. Lili (I had always called my sister by that name) made us sit in the parlour and brought us some warm tea. After we had exchanged some customary banalities, the children were brought out for us to admire. Annie was simply captivated by the little angels, and she held the baby girl as if she would not return her to her mother.

Seeing this, the proud mother impishly remarked, "You will soon have babies of your own, sister Annie."

This made Annie blush profusely and she dropped her gaze, not quite knowing how to reply. I threw Lili a look of reproof, but she pretended not to see it and, happily for Annie, artfully changed the subject. After the children were led away, Lili conducted us to Grandmother's room, telling us as we went that Grandmother had taken a turn for the worse. The doctor had been called to see her, but he had said that nothing much could be done. It would seem that Grandmother was not suffering from any sickness but that she was expiring from old age.

Lili opened the door to Grandmother's room and we stepped inside quietly. Grandmother was lying on a big iron bed in one corner. Only her wizened features showed above the bedsheet. Her thinning white hair spread like a fan on the pillow. Her eyes were closed and her face tranquil in repose.

As we approached the bed, I called softly, "Grandma...". When she did not stir, I called again and this time her eyelids flickered open, and her gaze fell upon us. For a moment, she just looked at us, then in recognition, a ghost of a smile appeared in her eyes. Her dry lips moved.

"Sze-Chuan... My dear Sze-Chuan... you've come." Her words were barely audible, and she spoke with difficulty.

"Yes, Grandma, and I've brought Annie to see you."

She turned her gaze on Annie. "Come nearer, my child," she said, her voice weak but clear. Annie obediently stepped forward. Her sweet nature could be seen in her manner. Sympathy welled up within her and shone in her eyes. And, as I had done, she called the aged woman, "Grandma." The old woman closely scrutinised her face for a few moments.

"Ah yes, the bride... the pretty, pretty bride." She spoke slowly. Then a look of intense sadness clouded her features.

"Oh, you're so pretty - it's pitiful... pitiful."

I was quite taken aback by such strange words, and I could see that Annie was too. Bewildered, she turned to me, but I was unable to help her. I, too, wondered what Grandma meant by those words.

"Sze-Chuan," Grandma was speaking again, "Sze-Chuan, make her happy. Always. Make your bride happy."

And with that, she turned away, murmuring the cryptic words, "Pitiful so pretty... pitiful pitiful "

Shaken and trembling a little, Annie and I preceded Lili out of the room. Back in the parlour, I immediately asked Lili what Grandma had meant by her strange words. I felt, somehow, that Lili knew, and I was determined to make her yield the information there and then.

"Lili, what did Grandma mean by what she said?" I asked.

"Oh, it's nothing really," she said, trying to sound casual. But I was not to be put off so easily. I had detected a touch of hesitancy in her tone, and was more convinced than ever that my intuition was correct.

"Come, come, Lili," I persisted. "Don't be evasive or you'll make me angry. I must and I will know why Grandma spoke so strangely."

"But it's nothing to worry about. Why should you make so much out of a little thing like that?"

"It's nothing to worry about! Grandma said it's pitiful that Annie is so pretty and you tell me it's nothing to worry about? Lili, how can you say that?"

"Husband - " Annie, in a small voice, tried to calm me down. But I had been well and truly worked up by then and would not desist.

"No, don't interrupt me, Annie. I intend to get to the root of the matter. I know I shall be really mad soon if I don't get an explanation for Grandma's enigmatic pronouncement. Well, Lili?"

Seeing my manner and in what mind I was, Lili realized that it would avail nothing to hold from me any longer what I wanted to know; and reluctantly, she yielded.

"I warn you, I won't be pleasant," she said. Then, as if from second thought, she went on, "perhaps it would be better if Annie does not hear what I have to say."

Before I could reply, Annie spoke up, gently but firmly, "Anything that concerns my husband concerns me," and turning to me she continued, "I must know anything that concerns us." I looked into her eyes and could not speak. But my heart went out to her and at that moment I believed that I loved her more than ever - if that were possible.

Lili looked from one to the other of us; and reading the answer in our face, she said, "Very well then, since neither of you can be dissuaded, I shall speak, much as it grieves me to think what pain and unhappiness my story will bring you."

She poured herself a cup of tea, seated herself on the sofa opposite us and took a sip or two from the cup while she pondered how best to begin. Finally, as if she had made up her mind, she put down the cup, looked at us again as if to satisfy herself that we really wanted to know the story, if indeed there was a story. Then she cleared her throat and began, addressing her words at me from the beginning, and indeed almost throughout the whole narrative.

"Neither of us ever knew Grandfather Po-Chueh. It never occurred to us to ask about him, nor did it occur to us why Grandma and Mummy and Daddy never spoke about him. All that the two of us knew was that he died many, many years before we were born, and we were content to leave it at that.

"Well, one day when I was ten and you were nearly nine, Grandma gave the maid, Old Li, a thrashing for breaking the antique porcelain vase she treasured so much. Do you remember? I felt sorry for Old Li and I crept into the kitchen to see how she was. I found her weeping in a corner, her face red, her hair dishevelled. I did not dare call out to her, fearing that Grandma might hear me, but moved quietly towards her. As I approached her, I found her muttering curses under her breath."

Lili paused to pour herself some more tea and as she did so, I noticed that her hand shook. She sipped the tea and, still holding the cup in her hand, resumed her story.

"I heard Old Li muttering... I could not hear everything, but heard enough to make out the gist of what she was bitterly spitting out. After calling Grandma all kinds of names, she said, "Serves her right her husband went mad and kicked the bucket when she was pregnant."

Lili, who had been staring into space while recalling the past, stopped at this point and looked directly into my eyes, whether for effect or to see if her meaning had been grasped I could not tell. But I was impatient for her to go on.

"Go on, go on," I urged her.

"Well, naturally my curiosity was aroused and I sought to obtain an explanation for what I had heard. I questioned Old Li but the harridan was in no mood to answer anybody civilly - I should have known that, of course - much less, timid little girls. She told me to go away and let her die in peace.

"I went away but I wasn't satisfied. I hounded Old Li every day and harried her for the story of Grandfather's death. But she would not divulge the secret. She just told me to forget it - which only made me all the more obsessed by it."

Here, Lili interrupted her narrative to say to me in parenthesis, "I didn't tell you what I had heard Old Li muttering that day Grandma beat her because I wanted to tell you the whole story after I had learnt all about it, so that I could show you how clever I was. You were always saying how silly girls were, remember?"

I wriggled uncomfortably in my seat, glanced at Annie out of the corner of my eye and gave Lili a dark look - all in the space of a moment or two. I thought it unsporting of Lili to bring in something which I thought she had no call to mention. But happily for me, Lili, who appeared not to have noticed my discomfiture, unconcernedly continued to speak, and Annie seemed too absorbed in the story to have apprehended the import of what Lili had just said to me.

"So I continued to pursue the matter relentlessly I wish now that I hadn't... Finally, when I despaired of getting the story from Old Li, I decided to approach Grandma herself. You remember how terrified of Grandma we were then? Well, it was quite some time before I had plucked up enough courage to approach her, despite the fact that my knees were wobbly.

"Grandma was dressing her hair when I entered her room. She turned to me when she heard me and asked what I was doing in her room. I gulped several times and, in a voice none too steady, I entreated her to tell me how Grandfather Po-Chueh died. I expected to have my ears boxed and to be expelled forthwith from the room. But, to my enormous surprise, Grandma, after staring uncomprehendingly at me for several moments, broke down and cried. I was rendered speechless by such unexpected behaviour on her part, and could only stand there in profound stupefaction. Then Grandma turned to me again and took me in her arms. Holding me close all the while, she told me through her tears about Grandfather Po-Chueh's death.

"I was very frightened by the time she had finished speaking. She made me promise never to tell you what she had told me, and I've kept that promise."

Lili had been speaking quite calmly throughout. Now her tone changed and became pleading, and it was clear that her mind was in turmoil.

"Oh, please, please, let me continue to keep my secret," she begged, on the verge of tears. "Please go away, and never think, never speak of this again!"

"Lili!" was all I could utter, once I had overcome my astonishment.

"Lili," Annie echoed, but more gently and more sympathetically. She rose and went quickly to Lili's side and placed a comforting hand on her arm. For a moment, I thought Lili was going to cry but she bit her lip and fought back her tears.

"I - I'm all right," she said, and her voice was quiet again. She soon regained her composure, but Annie remained at her side while she went on with her narrative.

"Grandfather Po-Chueh died in China when he was a very young man - just a few weeks before Daddy was born. He died in a very strange manner. Many people thought he had lost his senses. He walked about in a trance for days before he collapsed, senseless, in the garden. When they discovered Grandfather, they carried him into the house and put him to bed. He never got up again. He just lay there, unable to eat, unable to speak, only staring - always staring - into nothingness, until he died... With his eyes open, and wearing the same expression which he had been wearing ever since he went into that trance - an expression which gave everyone the impression that he was listening attentively to something or someone who was not there!"

Annie and I exchanged looks of wide-eyed surprise, and Lili looked from one to the other of us. Seeing the quizzical, attentive faces we turned to her, she took up her tale again.

"The cause of his death was not known, and it will never be known. But there was a story which went round the whole village and even spread to the neighbouring districts. The story went that, a few weeks before Grandma's confinement, Grandfather went hunting with some friends in the Ch'ien Tien district, north of the Wen Ho. While they were passing through a mountain village, they came upon a man, chained to two posts, who was possessed by devils.

"It happened that, at the moment the party came on the man, he was seized with a fit and, breaking his bonds, he rushed at Grandfather, snarling and clawing the air like a wild animal. Grandfather's horse bucked and threw him to the ground. Before he could get up, the maniac was on him and there ensued a fierce struggle. In a few moments, the madman, with diabolical strength, overcame grandfather, and, pinning him to the ground, began to strangle him. The others, who were for a time stunned and paralysed with the unexpected turn of events, quickly roused themselves and leapt from their horses to the rescue. But before they could reach the pair on the ground a short distance away (where they had rolled in their struggle), Grandfather managed to pick up a piece of rock from the ground and, raising it with both bands, brought it down with all his might on the madman's skull, which was instantly crushed by the blow.

"At that moment, a blood-curdling scream pierced the air, and a woman, heavy with child, rushed out from a nearby hut and flung herself on the body of the dead man, weeping and wailing loudly like some distressed animal. She held the shattered head of the dead man to her breast and gave voice to her grief, calling on the gods to avenge the foul murder of her husband. Grandfather, who had by this time picked himself up from the ground, had his face and garments spattered with the dead man's blood, but save for a few cuts and bruises he was not badly hurt, only very much shaken. Meanwhile, a crowd had gathered, and the people were excitedly talking and gesticulating and adding to the noise and confusion.

"After a few moments, the bereaved woman stood up and began to scream abuse at Grandfather, who was looking somewhat dazed. The woman then turned to the crowd of villagers and called on them to seize the murderer of her husband and to take his life in revenge. The voices rose, and it seemed as if the crowd was beginning to respond to the woman's call. Grandfather's friends made him mount his horse and, just as the crowd was taking up sticks and stones and preparing to make a rush at them, they galloped swiftly out of the village to safety.

"But the unhappy wife of the dead man had laid a curse on Grandfather's head. She had screamed, "Woe to you, Son of Hell! May you die a horrible death when your wife is big with child, as you've killed my husband when I am carrying his baby in my womb! And may a son of yours suffer the same fate every forty-seven years, for that is my murdered husband's age!"

Lili paused for a few moments while Annie and I held our breath and waited for her to go on. A strange sense of fear began to grip me, and beads of perspiration began to appear on my brow. Lili looked from one to the other of us, and finally rested her gaze on me.

"It is exactly forty-seven years since that hunting incident," she said.

There was a gasp from Annie. I stared, wide-eyed with shock, at Lili. There was a sustained silence during which no one moved.

Then a hoarse whisper escaped Annie's lips, "No!" And immediately after, she cried aloud, "No! I don't believe it! It's not true!"

She turned entreatingly to Lili. "Sister-in-law, say it's not true. Please! It's not true! Say it's not true!"

Lili did not move, and she did not answer.

But I knew the answer. I read it in her eyes. I knew the truth.

Annie flung herself on her knees at my feet, almost distracted with fear and uncertainty. Gripping my arms fiercely, she cried again and again, "Oh! It's not true! I don't believe it! It's not true! It's not true!"

Outside, it began to rain. It was getting dark, and the crickets had begun to sing. The sound of the wind in the trees was like the rustle of a woman's skirts.

Some days later, Grandma died, and was buried on an auspicious day.

The days passed into weeks, and the weeks into months. Annie and I never referred to Lili's story after the day we heard it. We tried to forget the whole matter and tried to behave as if it never happened. Annie's loving care and attention was of immense help in making me forget. She was like an angel to me.

When some months had passed, and nothing happened to mar our happiness, I began to feel a lightening of the weight on my mind. My spirits improved and I grew less and less worried and more and more cheerful. I began to doubt the truth of Lili's story. There were even times when I doubted if it had not all been a bad dream.

One thing was certain: Lili's story was slowly but surely losing its hold on my imagination. There were times when I went to bed and it did not unfold before my mind's eye and rob me of sleep. There were even days on end when the story did not intrude itself upon my bliss, and weeks when, if the story did occur to me, it did not fill me with the strange, almost uncanny fear that it used to.

And so the weeks and the months went by. Annie grew big and the time of her confinement drew near. The baby was expected to arrive in the early days of the eighth moon. I was very much excited over the coming of our first child. Preparations were made in the greatest detail. Some cloth was bought, and Annie began making baby-clothes. In the meantime, I started work on a cot of wood and rattan for the baby. The exact height and size of the cot was debated at length between Annie and me. In the end, it was decided that I should have the final say, and so the cot was made.

In those days, Annie grew more and more beautiful and seemed to be blossoming into the very quintessence of feminine beauty. At times, she was almost saintly in appearance, so sweet and radiant were her features.

The time of her confinement drew near. It was only a few weeks away now.

And then - it happened!

The Voice...

It spoke to me one night while I was about to drop off to sleep. For a moment I thought Annie had spoken to me and I called her name softly. But she did not reply. She was sleeping deeply.

I waited, tense and just a little frightened. My heart began to beat rapidly, and my hands grew cold.

Then the voice came again, out of the darkness above. A gentle voice, almost soothing. It spoke quietly, and had a fine quality about it. I thought it was a man's voice, but I'm not sure. It could have been a woman's. I don't know.

It spoke, and I listened. And, strange to say, as I listened, I ceased to be afraid and to be perturbed. Instead, I grew calm. A sense of quietness and peace such as I had never known before overcame me. It spoke briefly.

"Sze Chuan, listen to me," it said. "I am the bearer of good news. I have come from parts unknown to you but which I shall soon make known to you. Listen for me. I shall come again."

That was all. I listened and listened, but it did not come again. I fell asleep sometime in the middle of the night, and in the morning I began to wonder if it had not all been a dream. I did not tell Annie about it for fear that it might have adverse consequences on her in her condition. But I continued to listen now and then when it was quiet, to see if the voice would come again.

It did... in the afternoon, when I was taking a nap.

It took up precisely where it left off the night before and began to tell me about a strange and beautiful land in a valley of immense size - more than several thousand lis across. There, the trees and bushes grew in an orchard world of multi-coloured sweet-scented flowers and ripe, luscious fruits. Sparkling clear streams ran the length and breadth of the valley, and birds of exquisite plumage filled the air with their singing all day long. The air itself was pure and fresh, and had an almost intoxicatingly delicious quality.

When the voice had ceased speaking, I found Annie sitting on the edge of the bed, looking at me with a puzzled and somewhat frightened expression on her face.

"Sze Chuan," she said, when I looked at her. "I've been sitting here calling you for the last five minutes and you have not answered me, although you were not asleep. Is anything be the matter?"

Taken aback, I stared at her for a few moments. Then I said, "I'm - I'm sorry, my darling, I was... dreaming."

I decided on the spur of the moment not to tell her the truth. I knew she was not fully satisfied with my answer, but she did not press me for further explanation.

The voice came again that night. After that, it came again and again at odd times throughout the day and night. Sometimes it spoke when I was walking across the room, and I would stop where I was and listen. Sometimes it broke in on my thoughts when I was sitting and watching Annie at her sewing.

Once it spoke while I was having my dinner, and for fully a quarter of an hour I sat at the table listening to its magical words, while poor Annie (so I learned, from her later), almost distracted with anxiety and at a loss what to do, repeatedly tried to rouse me - in vain. It was now useless to evade Annie's questions but I could not bring myself to tell her everything, for she would not understand. How could she, when I myself did not? And it would only serve to worry her more. I told her that it was nothing, only that I was feeling a little unwell, and went to the bedroom to lie down.

The voice was coming more and more frequently and speaking for longer and longer periods each time. And every time it spoke, I listened. It was such a beautiful voice, and it spoke of such wonderful people and places and things.

Then one day, a few weeks after the voice first spoke, it began to speak and did not stop until several hours had passed. I do not remember what I was doing at the time but I feel sure that I was not in bed, where I found myself when the voice ceased speaking. Annie must have had me carried into the room and put in bed. As I lay in bed, the voice came again and again, and the times when I could hear or sense the presence of people in the room grew fewer and further apart. I was gradually slipping into a state of suspended animation - always waiting and always listening.

A few days after I had first found myself in bed, I lost the ability to move my limbs and could only lie motionless on my back. (I no longer ate or drank anything as I no longer felt hungry or thirsty.) The following day I lost my power of speech, and the day after that my ability to hear anything other than the voice, which spoke almost incessantly, now...

* * * * *

Oh, my husband, what has happened to you? Why do you not speak? And why do you not eat or drink anything? You no longer even look at me. The physicians have come and gone but they have not been able to do anything. They say they do not know what the matter is with you. How I wish I do! Why do you stare at the ceiling like that? Oh, my darling, the baby is coming, and you have fallen ill. You will not be able to greet it when it arrives. It is only two weeks before my confinement.

* * * * *

What's that? You say I can go to this beautiful land and live among all those wonderful people you tell me about? Can it be true?

Oh! happy, happy day!

Eh? Grandfather Po-Chueh is there too? How - how is that? Can people who - kill...?

Oh...

* * * * *

My husband - you are excited. I can see that. You do not move but I can see that. I can see it in your eyes. Yes? Yes? Oh, what can the matter be now? What can it be that you can see or hear, that makes your eyes shine so? Oh, why don't you speak and tell me what is troubling you? Why don't you tell me what you are thinking?

* * * * *

Oh, bless you! Bless you a million times for telling me that.

Annie! Annie, did you hear that? Did you hear what the Oh, how I wish I could tell you everything the Registrar has told me, Annie. How it would amaze you! How happy it would make you! Do you know that Grandfather is there in the Valley of a Thousand Delights? Do you know that he is known there as the Saviour of the Ch'ien Tien maniac? The Liberator of a Lost Soul? Yes, he freed the poor fellow's soul, not only from the Devil's shackles, but also from the prison of flesh. Did you know that this body of ours is really a cell that imprisons our soul? Well, it is. Until we discard our body, our soul cannot be free. And I'm going to be freed, Annie! I'm going to join Grandfather in the beautiful Valley of a Thousand Delights! How I wish you could come along too. How I wish I could free you from your prison!

I'm going now, Annie. I can't stay. They've come to take me away. Don't worry about me, my darling wife. Look after the baby. I'm going... Goodbye... Perhaps some day you will be able to join us. Goodbye ... Goodbye.

* * * * *

Sze-Chuan died two weeks before Annie's confinement. He had been lying in bed for more than a week - unable to eat, unable to talk - only staring, always staring, into nothingness, until he died ... With his eyes open, and wearing the same expression which he had been wearing ever since he went into that trance - an expression which gave everyone the impression that he was listening attentively to something or someone who was not there!

The Apostate

It was.. how long ago was it? Six years? Eight? Several years, at any rate, since I last saw him. We had been friends since we were at high school and although our beliefs frequently clashed, we remained the best of friends. He was a pleasant chap to be with: his conversation was always witty, and sometimes showed him to be remarkably well informed. I cannot recall a single occasion when I found his talk insipid or his mood depressing. He was always interesting. If he was gay, he was exhilarating; and if he was sober, his keen intelligence was positively stimulating. Intelligence - that was the quality of mind that differentiated him from the rest of us. He never once descended to imbecility, as so many of us all too frequently did. However, like all the rest of us, Harold Wong - that was the name we knew him by - had his failings too.

He was a sensualist. Which accounted, in part, for his indulgence in going to the cinema. Perhaps it explained also why he was a smoker of such long standing. He passed much of his time in the company of pleasure-seeking friends, regaling them whenever they sought him out (which was very often for he was extremely popular with them).

The last time I saw Harold, he was in the lounge of the airport terminus, saying goodbye to the swarm of friends who had come to see him off. He was leaving for England, having obtained a scholarship to study in a famous University there. I had barely sufficient time to say goodbye to him before he had to leave us and board his plane, which took off soon afterwards.

That was six years ago - or was it eight? Well, several years ago, at any rate - and in all that time I had not heard from him or from anyone about him. I had therefore forgotten all about him, and was most pleasantly surprised when I received a letter from him a few months ago. The letter came like a voice out of the past. This was how it ran:

Dear Goh Leong

You will be surprised to hear from me after all these years. I hope you don't have to search too long in the back-rooms of your memory before you remember who I am. I suppose I ought to apologise for not writing to you while I was abroad. But apologies aren't of much use, however. Explanations are what matter. But I won't go into that until you arrive.

I want you to come and stay the weekend with me. You will come, won't you? Finding the house may present some difficulty, but I am sure you will get here in the end. What you have to do when you arrive at Port Dickson is catch a bus or hire a taxi to take you as far as the sixteenth milestone down the Coast Road. There you'll have to alight and walk on the right hand side of the road for a hundred paces or so. Then you'll come to a footpath leading to the sea. The path is somewhat covered with grass, and thick bushes on each side have partly obscured the place where it begins. But you'll find it soon enough if you search carefully for it. Follow it and it'll lead you to the house.

I shall be expecting you. Please don't disappoint me.

Your sincere friend

Harold Wong

A stream of questions poured into my mind as I read and reread the letter. So Harold was in Port Dickson. Why did he return to Malaya? Why did he choose to stay in a place so far removed from the society and the social life that he loved? Finally, I gave up and, putting away Harold's letter, began to pack my things for the journey.

* * * * * *

"Hello! Goh Leong! How are you? I'm glad you've come. I was afraid you wouldn't." Harold shook my hand warmly and led me into the bungalow.

He had changed considerably in appearance. (I was to learn later that the change in his outlook was equally if not more marked). It seemed to me that he had grown taller without putting on more weight, and this gave him an appearance of leanness. But he was really quite well-fleshed and well-built. He had also acquired a darker tan but what struck me most was the change in his face. His handsome, regular features had become large and his eyes piercing. His thick black hair was long at the neck and the sides. As I looked at him, something very much like fear, some unaccountable premonition of evil, gripped me - but only for a moment. Then it was gone and Harold was speaking again.

"You must be tired after your long journey. Let me show you to your room and you can lie down for a while before you unpack."

"No, I'm not tired. Thank you. I just want to wash myself and clean up a bit."

"All right. The bathroom is over there, next to the kitchen. In the meantime I'll put your things in the room for you and you can join me when you're ready."

I thanked him and headed for the bathroom. There was a Chinese cook in the kitchen. He. looked up from his work when I passed him. But the glance he threw me was quick, furtive, almost, and he immediately lowered his head and appeared very much occupied with what he was doing. I was naturally surprised at this but I did not stop to question him as it might turn out that I had been mistaken. However, I was puzzled and in a thoughtful frame of mind when I stepped into the bathroom.

We were sitting in easy chairs on the porch after dinner. The bungalow stood on an escarpment that jutted out towards the sea like a forward-thrusting jaw. Rough-hewn steps led from the porch on either side to the short stretch of sandy beach. The spot was found in a cove-like inlet, with rocky cliffs to the right and left. With the thick growth of trees at the back, the house was neatly bounded on three sides with the sea in front. It appeared as though nature had shut out the rest of the world from this lonely spot.

The sun was low in the west and the sea was calm. The setting sun displayed its golden hues across the western sky and played them gently over the waves, just as a painter would do on his canvas. A gentle breeze played with the needle leaves of the casuarina trees and caressed our faces with its soft touch. The scene was a haven of peace and beauty.

"Well, Goh Leong," Harold began, "you must be bursting with questions you want to ask me. But before you shoot, I'd like you to tell me what you've been doing since I went abroad."

"There's really very little to tell, Harold. I taught at our old school, passed my normal, and settled down to the humdrum life of a school-teacher. And that's the job I'm still doing."

"Did you get married?"

"Why, no. Not yet, anyway."

"Which, I take it, implies that you're going to."

"Yes, I suppose. In due course of time. Don't you agree that marriage is the culmination of life and the fulfilment of the personality?"

"Maybe. Maybe not. It depends on whom you are marrying."

He was silent for a few moments, and seemed to be listening to something quite close at hand. The sun had set and night's insidious shadows were swiftly supplanting its last, weak rays. Above the raucous symphony of night sounds, the waves broke against the massive rocks at short, regular intervals, like a rhythmic, harmonious accompaniment to an unseen orchestra. The air grew cold suddenly.

"Shall we remove into the house?" Harold spoke at last, rising to his feet. I stood up too, and we went into the house and ensconced ourselves in comfortable armchairs in the big front room.

I waited for him to speak again. He closed his eyes and turned his head to one side, again in a listening attitude. The look on his face had taken on a grim expression. The muscles of his jaws worked visibly and he seemed to be waging some kind of war in his mind. It seemed a long time had passed when he spoke again.

"Listen!" he said, and his voice was urgent, insistent. "Listen to her, roaring like an enraged beast. She's always at it, night and day - the plucky girl. And she'll keep it up as long as rain falls and rivers flow. Listen! Did you hear? That was a mighty blow! A hay-maker. Oh, I love her for her spirit! She knows it's almost hopeless to try and break free, but she doesn't let that daunt her. Oh, no, not she! She lowers her head and comes charging as bravely as the bravest bull alive. She gives it all she's got, and each blow she deals carries with it all the force and impetuosity of a battering ram. She's a full-blooded amazon on the warpath, that's what she is!

I was awed by his imagination, and just a little frightened at the intensity of his feelings.

"You... you think all that of the sea?" I asked him, impressed.

"Yes, Goh Leong," he replied. His eyes flashed and his mouth was hard. "The oceans of the world embody for me the spirit of the lover of freedom. The ocean is bounded by the shores of the world, and it struggles incessantly against them as though they were bonds and it wants to break them. One would think that the ocean being so vast, it doesn't need more room to bustle in. But, no, the love of freedom is as limitless as space and therefore impossible of satiety. It is this love of freedom that has brought me to this isolated place."

"Do you mean to say that you came here... just to escape from the world?"

"No, not from the world, Goh Leong. From society. Society's a tyrant. It's also a prison. And it's from the prison that I broke free, and from the tyrant's hold that I escaped."

"But something must have happened to you to make you change your views so radically. What was it, Harold? You used to be such an amiable, sociable chap. How did you change?"

"Ah... how did I change? Well, that's the story of what happened to me while I was in England. I changed because of what they did to me; because they ruined my University career and didn't give me a moment's peace; because But I'm confusing you. I'm sorry. Let me start from the beginning."

He leaned back deeper into the folds of the armchair and his eyes stared into space. A glassy look came into his eyes, and I knew as I waited for him to begin that he was in the time machine of his mind, making the journey back to when it all began.

In the silence, the songs of the nocturnal insects rang in my ears, and seemed to increase both in pitch and in volume. And the sound of the waves breaking against the shore was loud and clear. Finally, Harold began his story.

"I was, as you well knew, a sociable, easy-going fellow. I was easy to get to know and easy to get along with. But I was also, you remember, living in the fast lane in many ways. I smoked and drank freely, and indulged in what you called the 'vices' to excess at times. You remember? But, of course, you do! How you used to lecture me on the infinite virtues of moderation and good health!"

His lips formed a thin, humourless smile, the second smile that he had given me since my arrival. It made me uneasy, and I twisted in my seat uncomfortably. Seeing this, and misunderstanding my movement, Harold went on quickly, in a voice that was almost kind.

"But you mustn't think that your lectures had fallen on deaf ears, Goh Leong. You failed to convert me to a different way ot life, but you did instil in me a love of honour and a respect for truth and justice which..."

He broke off and didn't complete what he was saying. I felt that he was keeping something back, but I didn't press him to tell me what it was. He looked away to avoid my searching eyes, and finished weakly, "I think I'd better go on with my story."

After a short pause, he continued:

"When I arrived in England, I slipped easily into the society I was to move in for the next two years. I suppose I did go a little out of my way to make sure that my future companions would have an instant liking for me - I still cared a great deal for the good opinion of my fellow men then. And I scored an instant hit with the company: they liked me from the start.

"It was a dizzy, tipsy world that I moved in. Bohemian, in many respects. We had frequent, secretly-held parties that sometimes developed into wild, all night orgies. We didn't escape scot-free with our excesses, of course. There were times when we teetered on the brink of being sent down. Two of our fellows were actually expelled in disgrace. But these measures only convinced us of the cruel injustice of society. We saw nothing harmful in our 'debauchery', as they called it, and we continued in it - with greater secrecy, it's true, but certainly with a vengeance. On the surface, we were as prim and proper as you please, but only on the surface. On the sly, we were a party of bacchanals and gay revellers. That was the kind of clique I associated with, and believe me, I thoroughly enjoyed it all - for a time. Then the Weatherbys came into my life.

"Sir Lionel Weatherby was one of the few millionaires left in England at that time. An industrial magnate, he was well-known in the locality for being a regular patron of the arts, and had the reputation of being a thorough good sport. He was a widower, and heirless, in his middle sixties, and had only recently taken a young Swedish bride to the amused interest of the - so far - indulgent public.

"I first met Sir Lionel at a dinner party in his beautiful Merryvale, one of the stately homes you read about in old books. I was taken there by a nephew of a friend of the old gentleman himself. The occasion was Sir Lionel and Lady Weatherby's first wedding anniversary. It was there, too, that I saw Lady Weatherby for the first time. She was tall, slimly built, with very fair hair and light blue eyes. Her features were wan and sallow, and there was an air of lightness about her. She moved with exquisite grace; and she played on the piano beautifully. A solo by Rachmaninoff. Beautifully.

"I could see that the Weatherbys were keen music lovers. Sir Lionel could talk of nothing else. When I got a chance to talk with him, I did most of the listening. And before long, Sir Lionel was very impressed with my keen interest in his favourite pursuit. When he invited me to spend part of the summer holidays with him and Lady Weatherby at his villa in Nice, I was fairly bowled over. I gratefully accepted his invitation, but without appearing to be too hasty in doing so. It was important to keep up appearances.

"Well, after that evening, the summer couldn't come too soon for me. And all those long, crawling weeks before summer, I spent on music. Music in books, music on the BBC, music in concert halls

"It was as though I was preparing for an examination on music. My friends were thrown aside for the time being. I left them to their pleasure-seeking, and devoted myself to music. Some of them grew bitter against me, but I didn't care. All my life I had entertained one great ambition - to travel widely and see as much of the world as I could. That was why Sir Lionel's generous offer was so very important to me. That was why I was prepared to risk falling out with my friends to make sure that I didn't disappoint my benefactor.

My holiday with the Weatherbys went by all too quickly. Unfortunately, Sir Lionel passed away not long after.

"It was at that time that my former friends turned against me. I couldn't understand why. I had nothing against them. What did they have against me? Anyway, they spread stories about me and Lady Weatherby. Once the rumours started, there was no stopping them. And the rumours became really vicious when they were taken up by people whose toes I had tread upon some time or other, and people who had always been prejudiced against me for reasons unknown to me.

"They said that I was an opportunist, a fortune-hunter. That I looking forward to Sir Lionel's early death for the chance of ingratiating myself into the good graces of his widow so that I could get my hands on the Weatherby legacy; that during the summer holidays I spent with the Weatherbys I'd already begun to scheme and calculate and shape my evil plans. And lots of other things, too, which I can't remember, but you can well imagine.

"It was then that the whole fabric of my beliefs and principles collapsed in a million pieces around me. My faith and ideals were shattered. The romantic concept of man and human nature which I had entertained blew up with the shock of a volcanic blast."

Harold's face grew hard as granite, and the curve of his lip spoke of the contempt and disgust that welled up within him. His voice grew harsh and bitter.

"For the first time, I was revolted by my fellow human beings. For the first time, I felt that man is a creature at once repulsive, hateful and despicable. I loathed and detested them all. I grew to hate them with a hatred I had not known before. I hated the gossip-mongers who greedily gobbled up and disgorged again the stories about me. I hated and despised those who weren't moved by malice, but who thought it great fun to exercise their imbecile wit on my predicament. They gave me no peace. They made life miserable for me. They shattered my world. The friends!"

All this had come out in a rush, in a flood of vivid memories that found words in an eloquence born of roused-up emotions. Harold was reliving that part of the past which aroused his strongest feelings. Now the storm in his heart subsided a little, and his breathing slowly returned to normal.

"That's why I finally decided to find a home in a remote and secluded spot, far from society and all its maddening influences. I chose this place That's all."

The story which Harold told was not uncommon; only the circumstances were unusual. The cause of his revolt against mankind lay in the painful and unhappy experiences he went through while he was in England. His hopes of a normal University life were irreparably dashed by the cruel tongue of malicious gossip. He was given no peace. When the widow of his late benefactor, to whom he had become attached, took her own life because of the scandal mongering and poison pen letters, he abandoned all hope of pursuing his studies further and left the country with the money which the deceased lady had bequeathed to him. For some years, he roamed the world in search of a place where he could build a home and find happiness in. At last, despairing of ever being happy among men, he sought refuge in seclusion and isolation.

As he finished speaking, Harold came back to the table and sat down in his chair again. A short silence followed. I was too engrossed in my thoughts to speak immediately. Harold's story had moved me, I was certain of that. I was sorry that he had been hurt so deeply as to renounce the world and all that it stood for: a home, friends, neighbours, community life. Life. He was renouncing life itself, wasn't he? As the thought occurred to me, I was moved to speak.

"Harold, I'm deeply sorry that what you've just told me should have happened. I know what you must have suffered and I'm truly sorry... I really am."

Harold made no reply, and I went on, "But can't you try to start again - here in Malaya? All is not lost yet. Dum spire spere. There's still hope."

"Hope!" Harold cut in, harshly, "Don't talk to me of hope. I don't believe in the word. There's no such thing. The man in a quandary who is foolish enough to hope is wasting his time. He would do better to conserve his energies instead of expending his forces in pointless hoping. For to hope is to fear and to wear oneself out."

It would have been pointless indeed to attempt to shake such a deep-seated conviction as Harold's appeared to be, and I did not belabour the point. Instead, I tried to break through his defences from another point.

"But it's... it's silly to throw up everything because you've been the victim of foul play at the hands of a certain group of people at a certain time in your life! It's like throwing in the towel at the first sight of blood. I should have thought you would be the last person to give in so easily, Harold."

"You don't understand, Goh Leong," Harold's voice was quiet but strong, his tone patient and patronising, as though he were explaining something to a child.

"It's not that I was running away from life - no, you don't have to deny it - that's what you implied, although you didn't exactly say so in so many words. I moved to this secluded spot not because I was afraid of life or of the evils I had met with in society. The windfall I received secured me from want and with the power that wealth commands, I could, if I wished, have set myself up in a comfortable and even enviable position for the rest of my life. No, I chose solitude and seclusion because I could no longer live happily with animals I loathed so utterly and uncompromisingly."

"But Harold! That was in England - so many years ago. All that is dead and buried now. Don't torture yourself with memories of the painful past. Try to forget. What matters is the now and the here and... and being."

"Do you really believe that people are different at different places on Earth, Goh Leong? You're more naïve than I could have thought possible."

He rose to his feet and paced the length and the breadth of the room as he delivered the tirade that followed.

"No matter how great the distance in space or time separating them, all men are odious, abominable beings! They stink - all of them - to a greater or less degree. What the world calls virtue, what it hails as honourable, praiseworthy and just, is no more than the whitewash on rotten beams. The mask, the façade. Inside, all is filth and muck and rottenness. All is selfishness and snobbishness and prejudice and arrogance. We talk of impartiality, but we only publish our hypocrisy and self-deception by doing so. When we protest disinterest, we only assert our bias and inclination. Don't talk to me of honesty and justice either. There is no honesty and justice in the world - only corruption and prejudice. As for truth - that is another of your so-called virtues which you mistakenly believe in. Truth! If there ever was such a thing, it's extinct now and has been for longer than we can remember.

"And the breeding grounds of all this spawn of humanity and the hell-houses you call cities, where all and sundry are heaped at random to make a filthy odious mass of muck and scum! Your cities are nothing but wild, primitive jungles teeming with vile weeds, creepers, parasites and vines - all savagely fighting and struggling with one another in a ruthless attempt to reach the top. No, sir! Give me none of that! I've had quite enough of your neighbours and neighbourliness."

Harold went on and on in this vein, carried along by the upsurge of passion. The force of his vituperation and scorn struck me such a blow that I was paralysed with amazement and - yes, fear. The towering passion of the man awed and filled me with horror. I even began to wish myself anywhere but in the company of this man. When Harold finally paused long enough for me to feel obliged to speak, I made a last feeble attempt to defend the life he reviled so bitterly.

"You.. you'll have real, lasting comforts in a proper home, Harold... You'll have fellowship and friends."

"Friends! The relationship you call friendship is the most shamefully abused thing in this vile world! The word has no more value than a cap which is put on or removed according to the climate and the place. The prosperous man is swamped with friends and often wishes that he has fewer. But the man in adversity is the loneliest soul in the world. There is no selfless, trustworthy and reliable person. The only people who can keep their word are dead ones. Friends!" The contempt in his voice as he spat out the word was indescribable. "No, Goh Leong, true friendship died with Damon and Pythias. There are only fellow-gossipers and commonly bored companions now, besides sponges and sycophants. Friends!

As I listened to this, it was on the tip of my tongue to refute what I felt was an unjust condemnation of friends and the way they changed. My friends were reliable and trustworthy. They were always true to their word and could be very helpful when called upon. Not one of them had ever let me down. Why, each of them would give his right arm for the other, if necessary. And I was sure that they would do the same for Harold if he could be persuaded to make their acquaintance.

All this came to me in an instant, and I was on the point of speaking my mind when it occurred to me how futile it would be - like trying to stop a flood with a handful of sand - and decided against it. It was no use. The man who stood before me was not the same man who left for England several years ago. I could not speak to him with the same assurance and certainty of being listened to and followed as I could with the other - the one who went away and didn't come back.

It was with a heavy heart and worried mind that I left Harold soon after, and retired to my room to snatch what sleep I could. But as I lay in bed.staring up into the darkness, a skein of thought crowded and confused my mind. The incoming tide had brought the sea so close to the house that the waves seemed to break against the walls themselves. The night insects seemed to retreat before this invasion of the sea, and the roar of the sea threatened to drown my thoughts. Sleep refused to be wooed and I turned and twisted in the bed almost in unison with the rolling, restless sea. The darkness around me was turning grey when I slipped into the folds of sleep.

It was late in the morning when I woke up, and the rest of the day passed quickly. Harold, at my bidding, told me more of his experiences abroad. I made him speak especially about his loss of faith in hope and friends alike, and he told me how he had turned to his friends for comfort and aid during the painful ordeal in England, and how they had failed and even turned treacherously against him. The event had been branded indelibly on his heart and mind, and he would never forgive the 'blighters' as long as they lived.

After breakfast the next morning, I packed my bag and prepared to leave Harold and go back to my home in and out of the world. Before I left, Harold handed me a letter in a sealed envelope addressed to the Manager of a leading Singapore bank, together with a cheque of over two hundred thousand dollars which he had signed and made payable to me.

"I want you to find my parents, Goh Leong," he said. "You know the house where I used to live. If they had moved, you'll have to trace them somehow, I'm afraid. When you've done that, I want you to cash this cheque - you might have to give them this letter, too, as I'm making the whole account over to you - cash this cheque, take half the amount for yourself and take the rest to my parents. You will tell them that I am living in some far-off country. What I'm doing, I don't want them to know. Say that I don't want them to find me because I want to be alone. You'll do that, won't you, Goh Leong? Please."

I assured Harold that I was most willing to take the money to his parents, but protested that I would not take a single dollar for myself. I simply could not accept such an offer, overwhelmed with gratitude as I was. Harold looked hurt at this, and I relented and said that I would take a small portion of the money, but not the entire moiety. He pressed me further, saying that his parents would be at a loss how to dispose of such wealth, but I was resolute and there the matter stood. When I asked him whether he wanted anything, he replied, "No, thank you, Goh Leong. I have everything that I want. You will remember you promised not to tell a soul about this place, won't you? I know you will. Goodbye and I thank you again for agreeing to carry out this task of explaining to my parents for me."

As I took his hand, I said, "I suppose it's no use asking you to leave this lonely existence and come with me, Harold?"

"It's no use, Goh Leong," he replied, quietly but decisively. "I'll never go back. Don't think of it anymore."

"I refuse to take that as final. I'll come back when I've settled the business with your parents, and I hope by then you'll have reconsidered my request and arrived at a new decision. For the time being, goodbye." And with that I picked up my bag and left him.

As I followed the narrow, winding path that led through the thick wood to the road, I had a curious sensation of having just left a lonely but reclusive retreat. I recalled that, some years back, I had read a book about some place in Tibet called Shangri-la, and I thought perhaps what I was leaving was that - to Harold. Then I thought of the noisy, turbulent, troubled world and began to wonder whether it was such a bad exchange after all.

"Sir."

The words, spoken in Cantonese, brought me to a standstill, startled. Beside the path just ahead of me stood a man. It was Ah Fatt, the Chinese cook.

"Sir," he said as he came up to me. "Sir, please - I must talk to you." He spoke in an urgent and insistent voice, but low and conspiratorially, as though fearful of discovery. He was a stout, well-built man of medium height and in his middle forties. His eyes had a frightened look in them.

"The... the boss. I think the boss is mad, sir. He's surely mad. Many times - at night - I hear him talking and shouting and walking up and down in his room. In the middle of the night, sir! And sometimes... sometimes he leaves the house and goes out into the darkness and the cold, moon or no moon. And sometimes, he doesn't come back till the next morning. And then he'd sleep away the whole day. One night, I followed him and saw him standing on the edge of the cliff and throwing out his arms now and then, like this (Ah Fatt stood with open arms in an attitude of welcome to indicate what he meant). I was afraid he was going to try to fly or something. I think he's mad, sir. He must be mad."

I did not question the sincerity or the truth of what the frightened man was saying. The terror it had inspired in him bore adequate testimony to his veracity. The revelation perturbed and made me anxious for the safety of Harold. It seemed that his solitude had begun to tell on his reason and sanity. I resolved there and then to do everything in my power to save Harold from the life which was fast reducing him to madness. But first, I had a mission to accomplish. Meanwhile, the frightened cook's fears must be assuaged.

"Perhaps he is a sick man, Ah Fatt. You must take care of him until I come back. I'll be back in one or two weeks' time. Then, if he is worse, we'll get him a doctor. In the meantime, you must look after him."

"The master... the boss is mad already," Ah Fatt was insistent. "He needs a doctor now. You must do something right away, sir. I'm... I'm afraid to be in the house when he talks and shouts at night. If it goes on much longer, I'll resign. I can't work for a man who's mad."

I felt that Ah Fatt's fears were exaggerated. Harold had been in full possession of his faculties in the two days that I had spent with him, and only his overpowering hatred and bitterness had given me any cause for alarm.

"Don't worry, Ah Fatt. And don't leave him until I come back. I promise you we'll do something about it then. All right?"

Ah Fatt agreed, though a little reluctantly. "All right. But don't be too long, sir."

I assured him that I would not, and went on my way. Throughout the journey back, my mind was occupied with thoughts of all that had passed in the last two days. And once again I resolved to do all that I could to restore my friend to a normal, happy life.

The day after my return to Kuala Lumpur, I went to look for Harold's parents in his old home in Sungei Besi. To my dismay, I found that his parents had shifted two years back, and that the present occupants of the house had no idea where they had moved to. The neighbours were equally unhelpful. There was no choice but to put a daily advertisement in the English and Chinese newspapers for the missing persons, which I promptly did. A week passed, and no news of Harold's parents had come in.

In the weekend, I took the train to Singapore and had Harold's money transferred to my account at the Chartered Bank in Kuala Lumpur. Then I looked up an old friend who knew a psychiatrist who could be prevailed upon to go up north, at short notice, if necessary, to attend to a very special.patient. The persuasiveness of money helped us to reach an agreement, and I made the return journey happy in the thought that I had taken a practical step towards securing the medical treatment that my friend needed. If Harold absolutely refused to go to a psychiatrist, he might consent to one coming to him.

Back in Kuala Lumpur, I waited another week for some response to the advertisements. None came. I extended the advertisements to the national newspapers, and offered a handsome reward for information leading to the discovery of the missing persons or of one of them. A third week passed and still no news arrived.

I decided not to wait any longer, but to pay another visit to Harold. I was worried about the state of his mind. What Ah Fatt had told me about his night excursions came back to me, and I felt that it would be dangerous to postpone my call any further. I had no news of success to report, but I could let him know what I had done, and tell him that I was hopeful of a positive result soon.

With these thoughts in mind, I made the journey to Port Dickson on a bright Saturday morning. From the town, I took a bus down the coast road and alighted at the place where the hidden path leading to Harold's house lay. I waited until the bus had turned the corner, and made sure no one was in sight before I stepped into the trees and found my way to the house.

As I broke from the clearing and came in sight of the house, I stopped in my tracks, amazed at what I saw. Ah Fatt, together with two other men, was preparing to fell the trees behind the house. Some thickets and bushes had already been cleared, and there was a distinct air of increased light and openness in the place. After the first effects of surprise had worn off, I called to Ah Fatt, intent on finding out the meaning of what was going on.

"Ah Fatt! What are you and these men doing? Did your master give orders for those trees to be felled?" The man did not speak for a moment, looking guilty. I began to suspect some foul play.

"No, sir," he replied, half-defiantly. There was something odd, something rather puzzling about the man's manner which struck.me as strange. My suspicions increased.

"Well?" I demanded impatiently. I was determined to get at the root of the matter. "Speak up! Where is your master? I'll report you to him this instant."

The man did not answer immediately. He seemed undecided how to begin. With an impatient gesture, I swung round and headed for the house, calling loudly for Harold to come out.

"Harold! Harold! Are you there, Harold?" I was about to step into the house when Ah Fatt, who had followed close on my heels, came up and stopped me.

"The boss is gone, sir," he said. "He went nearly two weeks ago. He he left the house to me."

I stood shocked and incredulous. My countenance must have depicted my unbelief, for Ah Fatt went on to explain his astonishing words.

"One afternoon - ten days after you'd gone - the boss left the house and came back in the evening rowing a sampan, which he tied to that tree there. I don't know where he'd got it, sir. He just came back in it that evening. Then the next day, after the sun had gone down, he said to me, 'Ah Fatt, I'm going away and I won't be coming back. The house is yours. You have been a good servant, and I want to reward you by giving it to you. Goodbye.' And then he started to go, sir. I didn't know what to do. I asked him where he was going, but he didn't say. Then I asked him whether he wanted to leave a message for you, sir, and he said, 'Just goodbye'. And then he rowed away and hasn't come back. He left me the house. He said so. I'm turning it into an hotel."

I was too overpowered with amazement to speak. For a few moments, I stared at Ah Fatt as though he were a monster out of some horrible nightmare. Frightened by my looks, he shrank away, mumbling fearfully, "He left me the house. He said so. He said he wasn't coming back. He was mad, sir. I told you he was mad. I told you."

I told you he was mad... I told you he was mad... I told you I told you ... The words, each a sledgehammer blow, echoed and re-echoed in my head. I told you, I told you, told you, told

I found myself on the beach, staring at the expanse of sea before me. The tide had receded, and the rocks to the right and to the left stood out naked, jagged and angry - all pointing their finger at me.

I told you, told you, you, you...

Not a speck could be seen on the horizon. They must have found the sampan now. And the body? It too must be washed up somewhere by now. Unless he tied something heavy to his feet.

Harold had found the freedom that he loved. Forever.

That was six months ago. The advertisements having brought no result, I discontinued them, and turned to the police for help. So far, nothing has come up.

Meanwhile, the man who was a cook is now the proud proprietor of a flourishing hotel in Port Dickson, and I am the unhappy possessor of more than two hundred thousand dollars, not a single cent of which belongs to me.

The last friend to whom Harold turned had failed him.

COUNTRY LIFE

Oh, for a cottage perched atop a hillAnd looking down on a valley of green,

Where roses growing beneath the window-sill

Are the loveliest the sun has ever seen.

Give me a land where the rivers run

Through lush green fields and rolling downs,

Where song-birds sing, and rabbits, in fun,

Leap through thickets and across grassy mounds.

I don't want the city, its noise and bustle;

I don't want machines and smoke and dust.

I shudder at the screech of a steam whistle;

The blare of horns all but makes me "bust."

Give me a land where the skies are clear,

Where the air is pure and fresh and sweet:

Give me a spring with a greenwood near,

And a little pool where the swift rills meet.

You can have your towns and what you will

But give me a house, petite and clean,

Where roses growing beneath the window-sill

Are the loveliest the sun has ever seen.

WHERE CLOUDS ARE BORN

Away in the mountains up so high,Where mist the mountain tops enshrouds,

There's a valley where the breezes sigh,

In the secret birthplace of the clouds.

I went there once on a morning bright,

And I saw the wondrous magic birth;

And I watched the wraith-like wisps of white

Rise from the fresh sweet-scented earth.

The rain that had washed that world of green

Had ceased to feed the glutted streams;

Black clouds in the sky no more were seen,

And the sun appeared with smiles and beams.

Nature that had slept was now awake:

Birds that were stilled their songs began;

Dragons with butterflies in their wake

Came out to play, as only they can.

The very air seemed to become alive

And pierce the nostrils headily,

And with th' music of the spheres connive

To intoxicate me steadily.

It was then that I stood on the valley's rim

And looked in awe on the valley's floor,

And all around at the landscape grim,

And felt so small, so tiny, and poor.

And then I saw that from the rocks and earth

Arose a cloud so white and light;

And it sought the sky, its gift at birth,

And before very long was lost to sight.

Other clouds followed upon its tail

And traced a path along the sky;

And drifted away all under full sail,

Making me wish that I could fly.

Thus pleasantly did I pass the day,

Watching how the clouds are born;

When at last I sought my homeward way,

Many hours were gone since the morn.

I was a-weary, but I was happy,

And a knowing look was on my face;

For I had solved a great mystery,

I had seen the clouds' birthplace.

A DEATH WISH

I see it allI hear the call

Of Death's sweet thrall

"Abandon all."

Once I had faith

"The Lord God saith -"

But hope's a wraith

And now - no faith.

So that they call me heathen

Deny me heaven

Urge me the leaven

To seek if I seek heaven.

I am the Resurrection -

Whosoever -

Am I my brother's Keeper?

Neighbours and brothers

Do unto others -

Who is my neighbour ?

Sell, give, and come follow me

Arduous is the way -

Alas, committals bind me

Excuse me, pray.

So that the heart constricts with pain

So that, though shocked, you know it's vain

Vain though you try and try again.

O come take me

O come deliver me, sweet Lethe!

THE PRISONER

I began in an agony,In an agony in a cell.

And I thought once I'd broke free

All would always be well.

But no -

I find to my misery

As on life's journey I go

That wherever I may be

I'm in prison.

And no sane person

Will for one moment even

Think he's free.

THE LIBERATOR

It's funny -It's funny that men should fear

That which will come to make them free;

Funny that the sick and in pain

Should strive to be well again

Only to know more pain -

All is only misery;

That the oppressed should keep on fighting

As though life were really worth living.

It's funny -

That when the only person

Who can free us from this prison

Makes his entry

We should make our exit

Without knowing it.

It's funny - funny.

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 14 September 2000.