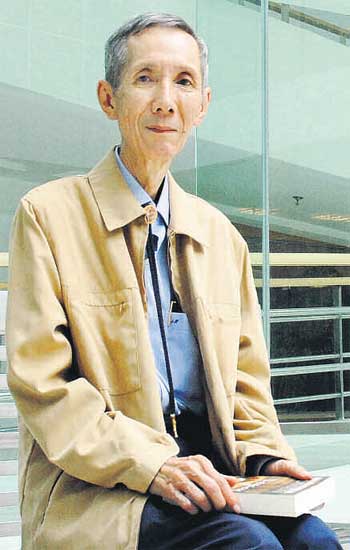

Shariza Hussein was a Victorian from 1956 to 1962. He participated with the VI contingent at the opening ceremony drill at the Merdeka Stadium on 30 August 1957. After his H.S.C., Shahriza was awarded a Colombo Plan scholarship and read for his B.A. Hons and Dip. Ed. at Monash University, Melbourne. He taught at Alam Shah Secondary School for four years. He served the Education Ministry as Exams Specialist and Curriculum Designer. In 1977, Shahriza left for the private sector to set up a publishing firm which he operated until his retirement in 2005. Legacy is his first novel and he is working on his second literary effort. Resident in Petaling Jaya, he is married to a Thai academic and has two daughters and four grandchildren. Following is an extract from Legacy.

PART IV: BRITISH MALAYA

November 1918

The obituaries in The Malay Mail and The Straits Times seemed unending. Day after day the names of men and women, young and old, Europeans and Asians alike, were printed and read and grieved over. The names of the Muslim dead were never made known in such a public manner, of course, the sad news being spread by word of mouth, through hand-delivered messages and by telegram. Despite that, more than two hundred people attended Mansur's funeral rites at his home in Gopeng and at the local Muslim cemetery.

The end had come quickly for Mansur, as it had for twenty-five thousand others in the FMS in the months before. The Spanish Flu epidemic that circled the globe took its grim toll, killing millions of people, many more than all those who had died in the battles of the Great War. In the United States alone over four million people succumbed to the epidemic. Twenty-five million people perished throughout Europe while India alone lost twenty million souls. Striking as it did towards the end of the greatest slaughter the world had ever known, the epidemic was widely regarded as God's punishment for Man's sins.

Mastura was a figure of solemn grace throughout the day of the funeral, receiving the condolences of friends and acquaintances, many of whom had rushed from Kuala Lumpur, Ipoh and Penang. Mansur's burial was delayed for a full day - a departure from the Muslim custom of burying the dead as soon as possible in order to enable them to make the journey.

Aishah and Khatijah had arrived in Gopeng two days before Mansur died. Aishah's twins, deemed still too young to travel, much less understand the import of the event, had been left behind in Kuala Lumpur in the care of Aishah's trusted servants and the women of Haji Sahar's family. Despite his age, Haji Sahar insisted on driving Aishah and Khatijah himself in his new motorcar.

The day after the funeral, when most of the guests had left for their homes, Mastura sat with her daughters in her bedroom. Not a word passed between them for half an hour. Each sat quietly on the floor, her eyes on the intricate patterns of the Persian carpet. Once in a while Mastura would look up and glance around the room, taking in the items and pieces of furniture she had shared with her beloved Mansur.

She had been with him in the final hours of his life. Mansur had alternated between delirium and fitful slumber. But always, whenever he was conscious and yet incapable of coherent speech, his eyes would be on her and they would be brimming with love. Mastura held back her tears as hard as she could.

Sometimes she heard him speak during his delirium. But she could not make out the words. But she knew he was deeply troubled, and she knew the reason why.

"Be at peace, my love," she had whispered to him, over and over. "You did nothing wrong. If anyone sinned, it was I, not you. Find peace, my darling husband."

Mastura thought back to that day two years earlier. Mansur had returned from Kuala Lumpur in a highly agitated state. He had told her about Steven Toh's reappearance and Robson's problem. The two of them had sat through an entire day, going through the alternatives over and over, only to arrive at the same terrible conclusion.

But Mansur had vacillated, beset by doubt and conscience. As the days passed, he began to suffer bouts of depression. When his health also began to deteriorate, Mastura knew that she was the one who had to act. But she also knew the price. It was one she was willing to pay.

As though in a trance, Mastura went to her bedroom wardrobe and brought out the wooden casket as she had done so many times before. She took out the timepiece and begged forgiveness of its owner for what she was about to do. She kissed it and put it back in the casket.

She knew she would never hear from her dear James again.

That same evening Mastura had a quiet talk with Yap Thiam Sah. Two days later, she gave him the thousand dollars that he said the job would cost. After that there was nothing but the wait.

At the end of the month, the Singapore police found the body of a well-dressed Chinese man in an alley. All the signs indicated armed robbery, not unusual in that part of the city. An attempt was made to identify the victim. And as happened so often, there was no way of doing so, as the victim had no papers on him. It was a month later that word reached Robson and Iris that Steven's parents had lost contact with him. Steven had disappeared once again.

And now, sitting with her daughters, Mastura felt a loneliness she had long forgotten, felt again the isolation and despair, and yes, anger even, at the loss of one she loved. Was Mansur's death some kind of divine retribution, punishment for the murder she had arranged? She could not be sure.

After what seemed an eternity, Mastura rose and walked towards the wardrobe. She unlocked a drawer, took out something and returned to her daughters with a box in her hands. It was a wooden casket, its surface decorated in the Majapahit style. She handed it to Aishah, who looked at her questioningly.

Open it, Mastura said softly.

The timepiece gleamed softly in the subdued light of the room. Aishah took it out of the casket and looked intently at its open face. The hands were showing the wrong time. The watch had stopped working, for how long Aishah didn't know.

"English," she pronounced as she examined it. She looked up at her mother. "Is it Father's?"

Mastura did not answer. Her mind was elsewhere, to another place, another time, another man. A smile played on her lips as she remembered. He would check the time often as he waited for Abdullah, tardy as usual, to enter the audience room. He would consult the timepiece impatiently as he waited for the Naga to convey him to his next destination and yet another of his thankless tasks. But he never took out the timepiece whenever he was with her. It was as if he wanted time to stand still.

"Mother?" Aishah said gently.

Mastura blinked a couple of times and returned to the present. It was some moments before she spoke.

"I'm sorry, Esah," she said softly. Her expression was serene. "I was remembering that night in Karai. The cool night air, the soft chirping of the insects, the wafting fragrance of the chempaka blossom. And your father. I never knew what love was until that magical night."

That s not entirely true, her inner voice told her. You knew love once before. A different kind of love, to be sure, but love nevertheless.

"And Father gave you this watch?" It was Aishah again.

"Read the inscription on the back," said Mastura, her voice barely above a whisper.

"J.W.W.B? Ceylon? Mother, whose watch is this?" asked Aishah. Khatijah leaned forward to look.

"The initials are those of James Birch, the first Resident of Perak. It's his timepiece."

"What? How?" Aishah stammered. Khatijah was equally wide-eyed.

"That watch also belongs to Ijah in a way," Mastura continued. As Khatijah looked up, startled, she added, "It was among the presents that attended the marriage proposal between Ijah and Deraman, a son of the late Datok Maharaja Lela."

A moment of stunned silence.

"How did you get to keep it?" asked Khatijah at last. She slowly turned pale as the truth began to dawn on her. "No, Mother, don't tell me!"

"Yes, Ijah, I accepted the marriage proposal. Sultan Abdullah himself presented the suit on Datok Maharaja Lela's behalf. I could not refuse. Besides, it was the only way I could keep the timepiece."

"But why would you want to keep it?" asked Khatijah incredulously. "You could have bought any number of timepieces like this. Why this one? Why a dead Englishman's?"

"He was not any Englishman, Ijah," Mastura replied quietly. "He was special."

Silence reigned once again after Mastura finished telling her daughters about James Birch, Sultan Abdullah, his corrupt and cruel chiefs and the miserable, downtrodden land that was Perak in the previous century.

Silence reigned once again after Mastura finished telling her daughters about James Birch, Sultan Abdullah, his corrupt and cruel chiefs and the miserable, downtrodden land that was Perak in the previous century.

It was Aishah who broke the silence. "Why are you showing this watch to us now, Mother?" she asked gently.

"I have kept this timepiece for more than forty years. In all that time it has helped me find my way through the rough periods of my life, helped me out of the darkness. It has given me hope when I saw only despair, given me answers when the questions seemed to have none. Your father disapproved, of course, calling it idolatry. But we women have special needs, do we not?"

Mastura was relieved and gratified when both Aishah and Khatijah nodded their understanding.

"I am showing the timepiece to you now," Mastura continued,""because I am passing its safekeeping to you. I vowed to return it. Now that task falls on the two of you."

"Return it?" asked Khatijah. "But how?"

"You will know when the time comes," Mastura replied.

"But why give it to us, Mother?" Aishah asked. "Why don't you keep it? You will need it even more now that Father is gone. Then, when the time comes, you can return it yourself."

"No, Esah. I have become unworthy," Matura replied simply.

Aishah and Khatijah waited for an explanation, but their mother would say nothing more.

October 1920

Aishah arrived at the appointed time and made her way up to the headmaster's office. She identified herself to Pavee, the school clerk.

"Ah yes, Puan Sharifah," said the young Eurasian politely. "Master Shaw is expecting you." He knocked softly on the adjoining door and at an indistinct acknowledgement from the other room, opened it. "If you'll please go in, Puan?" he invited

Shaw's office was what Aishah expected of an academic's study. Books and file holders filled the shelves to overflowing, framed certificates occupied the available vertical spaces, and sports trophies were crammed in the large glass-paned cupboard. But the rosewood work desk was tidy, with no more on it than writing pad, an ink well and pen, and a few paper files stacked neatly on one side.

Bennett Eyre Shaw, M.A. (Oxon), headmaster of the Victoria Institution, rose from his swivel armchair, came around the desk and extended his hand with a friendly smile.

"Ah, Puan Sharifah, it is indeed a pleasure to see you again. It has been almost a year, I believe, since we last met," he said pleasantly. Gesturing to the chair set across the desk from his, he added, "Please have a seat, Madam."

Aishah returned his smile as she took his hand. His handshake was gentle, almost like a woman's, as she remembered.

"And I am pleased to see you again, Mister Shaw," she replied and settled down in her chair. "Yes, it has been a long time."

The headmaster inclined his head, resumed his seat and faced her.

Aishah remembered the last time they met. It was at a party thrown by Choo Kia Peng, executor of the late Loke Yew's estate. The party was held at the Peninsular Hotel, originally the palatial mansion of Loke Chow Kit. The hotel's location just behind Kuala Lumpur's popular watering hole, the Selangor Club - fondly dubbed "The Spotted Dog", purportedly because membership to it was open to all of the town's different communities - spoke volumes of the wealth and prestige of the town's Chinese business elite.

Aishah had been invited to the party not so much because of her standing in the Muslim business community as for close her friendship with Loke Yew's widow. Aishah had helped Madam Loke with the difficult delivery of her son, Wan Tho, five years earlier and had earned the matriarch's everlasting gratitude. The lady also swore by Aishah's remedies over Western pills and liniments for her various aches and pains, real and imagined. Towkay Loke Yew might have sometimes dressed and disported himself like an English gentleman in public, but at home his lifestyle and that of his family remained very much traditional Chinese, in his case a Cantonese mandarin. Madam Loke Yew herself believed firmly in Chinese and Asian medicines.

Several of Kuala Lumpur's European expatriates had been present at the party, even though on that particular occasion - to celebrate the opening of a new trading company within the Loke Yew business empire - none of the senior government officials had been invited. It was very much a commerce-linked event and the guests were mainly business associates - bankers, planters, miners and merchants from the town s different communities. Bennett Shaw had been included in the guest list because Loke Yew had been one of the Victoria Institution's founding fathers and several of the town's important personages had once been Shaw's pupils.

Aishah surveyed the headmaster's room, her eyes dwelling casually on the framed certificates and the trophies. She felt comfortable with Shaw, having known him for some time, if not all that intimately. Apart from a couple of social occasions, and both times with John Robson as her escort, Aishah had had little contact with the academic. This was her first visit to his work place.

"Is it as you expected?" asked Shaw, watching Aishah with a mildly amused look on his face.

Aishah blushed prettily. "Forgive my rudeness, Master Shaw. But this room reminds me of my late father's study." Then, a little mischievously, she added, "Actually I was thinking of how different your office is from Mister Robson's. Yours is far tidier."

Shaw laughed. "That, my dear lady, is because John's a newspaperman. His kind thrives on clutter - organized disorder, as he prefers to call it. But I, alas, have to live up to what the public expects of an academic. Ordered and dull."

"But you should see the study in my bungalow," he went on. "Even I can't find my way around the mess there. The bane of confirmed bachelors, I'm afraid."

Aishah beamed him her most charming smile. She liked Shaw - a true English gentleman, unfailingly courteous and friendly despite his somewhat patrician demeanor. He was also unattached and Aishah could not resist teasing such men. That was why Father Andrew of St John's Institution always got a ribbing from her. Despite her liberal outlook, Aishah never could comprehend celibacy, not among robust, healthy males. But she didn't know Shaw all that well to tease him. "I'm sure you exaggerate, headmaster," was her demure reply.

"So how goes life in fair Kuala Lumpur?" Shaw asked, quickly moving to safer ground. "I've been back only a couple of weeks. I'm afraid I haven't had the chance to keep track of local goings-on, what with so many things to take care of here at the school."

Shaw had just returned from his latest home leave, the long furlough in England usual for British expatriates after every few years of service and for many of them a welcome respite from the rigours of working abroad. Shaw had been the headmaster of the Victoria Institution since the school was established in 1894.

"Oh, life is as usual. No major floods and no riots while you were away, I'm happy to say. And no scandals worth talking about. But we're all glad you're back, Master Shaw. Madam Loke frequently asked after you. I trust you had a pleasant home leave?"

"It was a welcome sabbatical, although I must admit I missed Malaya's warm climate after the first month," replied Shaw with a rueful smile. "I've been far too long in the tropics, I fear. Blood's gone a bit thin. I feel much more at home here than in England."

Shaw's thoughts went back to Britain's depressed state after the Great War - the massive devaluation of the Pound Sterling, the shortage of practically everything, the relatives and friends lost in the trenches of Flanders, and the survivors, now crippled or emotionally scarred or languishing on the unemployment list. There had been times, seeing the aftermath of the war in his village in Surrey, when he regretted going home at all.

The academic returned to the present with an effort. "Do forgive an old man, my dear lady. My mind was elsewhere for a moment. But I'm forgetting my manners. Would you care for a cup of tea? I bought the new blend Fortnum & Mason came up with." He began to rise from his chair.

"Oh no, thank you, headmaster, it's most kind of you. I wouldn't want to take up too much of your time. So I think it's best that I get to the point. I've come to see you about my sons. I would like to enroll them at your school."

"But of course," replied Shaw. "Victoria Institution will be happy to have them. Your twins are now what? Nine? Ten? And from what I've been hearing about the way you've educated them up to this point, they can enroll in the Prep School without any problem. Why, they might even be able to join the Middle School.

Aishah instantly perked up. How did Shaw know Hamid and Hashim were twins? Or how old they were? Or how they had been educated? She had never told him any of these things.

If Shaw realised the faux pas, he did not show it. But he noticed Aishah's enquiring look and knew he had some explaining to do. He cleared his throat.

I see I owe you an explanation, Puan Sharifah, he began tentatively. "It's not that I'm the prying sort, you understand, but I owe it to my profession to keep an eye out for promising youngsters. This school's reputation is built on quality material and many of its students are now men of high social standing. Take 'em in young, train 'em well and they become useful citizens, I say."

"As well," Shaw went on, as Aishah nodded but continued with her bemused, if slightly skeptical look, "I've always been keen to increase the number of Malay boys in the school. There have been too few of them in proportion to this town's native population, don't you agree?" Shaw flushed slightly as he realised how lame his explanation sounded.

Good try, headmaster, Aishah decided. But no, there has to be something else at work here. Her sons' enrollment at the school has been expected, if not in fact desired. Someone clearly wants them to be in the Victoria Institution and not some other school. But who could that be? And why?

Aishah had briefly considered sending her sons to The Malay College in Kuala Kangsar. Malay boys were being given a good English education there. But enrolment in that residential school, established in 1905 immediately after Swettenham retired, was restricted to children of royalty and the aristocracy. Aishah felt her sons might get in on the strength of their pedigree, but that pedigree was a convoluted one, even if Khatijah was confident that she could get her nephews admitted on her standing in the Perak royal family. But Aishah had decided that getting her boys into the College that way would be like entering through the back door. She, and certainly Mastura, would have none of that.

"Well, Master Shaw, I'm sure Hamid and Hashim will be happy to contribute towards increasing the Malay population of your esteemed school," Aishah said softly. If Shaw detected the mild barb in her words, he gave no sign.

Aishah decided to test the waters a little further. "But silly of me, I'm forgetting. I have here a couple of letters of recommendation," she fumbled with her handbag.

"Oh no, those will not be necessary, my dear lady," said Shaw. "The fact that you are the boys' mother is recommendation enough!"

Realizing the trap he had fallen into, Shaw trailed off and gave her a sheepish grin.

"What a gallant thing to say, Mister Shaw," Aishah said sweetly, her suspicions confirmed. Time to let the poor man off the hook, she decided. "But I've taken up so much of your valuable time, headmaster. So if you'll excuse me, I'll take my leave."

She rose from her seat, immediately followed by a very relieved Bennett Shaw.

"It has truly been a pleasure talking to you, my dear lady," he said as he escorted her out. "I shall have Pavee send you the necessary forms for your sons' enrollment. The new term does not start until January, which should give you ample time to make the necessary arrangements. Goodbye."

Shaw stood on the verandah of the school's upper storey and watched as Aishah got into her car and the vehicle puttered slowly up High Street towards the centre of town. He did not turn his head as his companion joined him.

"Well, Bennett, that went well, considering," said John Robson, an amused smile on his face.

"I lost it twice, I think. She's a really sharp lady.

"You're right on both counts. But I blame myself, I should have prepared you. Still, what matters is that the Old Man's going to be happy."

"Well, I'm not good at subterfuges," said Shaw a little testily. "There was absolutely no necessity for this charade. I would have accepted Sharifah Aishah's boys gladly through the normal procedures."

Then, somewhat sulkily, he added, "Why doesn't the Old Man tell her outright that he wants her sons in my school?"

"That wouldn't do," replied Robson. "At least that's what he thinks. As you may have noticed, Sharifah Aishah's a person who knows her own mind and doesn't like being managed, however well-meaning the intention. Besides, she and the Old Man have never actually met."

"Oh?" Shaw was surprised. "One would think!"

"Yes, it's a curious situation," responded Robson to the look on his friend's face. "I don't quite understand it myself. But it's certainly not some secret admirer lurking in the shadows, if that's what you're thinking."

"The thought did cross my mind, unworthy though it is," said Shaw. "She's a handsome enough lady. But why did the Old Man pick my school in particular? Surely as headmaster I'm entitled to know at least that."

"I don't know, the Old Man didn't tell me. But I think it has something to do with his not wanting Aishah's boys to enter the Malay College.

"Why ever not? The Malay College is an excellent school, with good teachers, some of whom I know personally. Eton of the East, they call the College, although I for one disagree, of course. And if the Old Man thinks I'll still be around to see the boys through their education, he's very much mistaken. I'll retire in two years' time."

"He has his reasons, no doubt. Something to do with a promise made long ago, I don't know what or to whom. But I do know that the Old Man's involvement with Sharifah Aishah's family - mostly from a distance and with almost complete anonymity, I should add - goes back almost half a century. I think it's a story worth writing down, once I have all the facts. That'll have to wait till the Old Man's dead and gone, though. I might get sued for invasion of privacy otherwise."

"Well, I'm not wishing for the Old Man's early departure from this earth. But I'm no spring chicken and I certainly want to be alive to read your book!" laughed Shaw. He consulted his watch. "Now toddle off, John, I have some paperwork to finish."

Robson was deep in thought as he picked his way around the food vendors ranged along the school perimeter fence. He absently hailed a rickshaw as soon as he found a space along the busy High Street, got in and gave his destination in fluent Cantonese. He settled back in the seat, oblivious to the sights, smells and sounds around him.

Yes, the conversation in Shaw's office was becoming a trifle awkward, he thought. Poor Bennett! He was outflanked and trumped. But how much does Aishah suspect? She's surely astute enough to suspect I had a hand in it - Shaw practically presented that to her on a platter. I'd better prepare myself for some hard questioning. Have to watch my step - she must not find out about Swettenham's part in all this.

Ah, Frank Swettenham! How old is he now? It's been fifteen years since he was put out to pasture, with a KCMG to keep him happy, and numerous books and lecture papers on Malaya to his credit. Lesser men would be content to potter around in an English country garden at his age. But he still ranges the Malay states on a regular basis, like he owns them. Or, perhaps more correctly, like he owes them.

What was it he once told me, all those years ago? It was at the Selangor Club after the party to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII. We are a dying breed, he said. Like the Gods of Olympus, we will soon be gone and forgotten. And what we sought to accomplish, whatever noble mission we embarked on, will be diluted like some abandoned stengah and handed over to younger gods. And they, engrossed with themselves, will be uncaring deities.

Well, the new gods have already arrived, Robson thought sadly - the bright-eyed, snot-nosed graduates of the Colonial Service exams, the new generation of young Britons eager to claim their place in the sun, jockeying for position and prestige, building and tenaciously holding on to a world of privileged existence of their own making or imagination. They are the new class of masters, but masters through their insistence that they should be treated as such, not through respect earned from selfless service.

Robson recalled how he had not quite understood what Swettenham had meant then. Now it has become so clear. The British in Malaya have truly become a class apart, elevated, venerated, and isolated from the country's brown and yellow masses. They are the Olympian gods who no longer deign to come down from their mountain. Well, the day will come when the people of this country will no longer need such gods.

"Daddy! Daddy! Mama, daddy's home!"

Robson bent down as his two children ran into his arms. Iris was standing at the door of the bungalow, her face wreathed in a welcoming smile. He smiled back and walked towards her, his children clinging to his arms.

"Hello my love," he said brightly. "What's for lunch?"

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 23 April 2008.