"Gay Prowlers on Victorian Mounds!"

And then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel,

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school

nwillingly' certainly did not apply in my case, though by

the time I got to Senior One in 1950 and had to come face to face with my

Victorian nemesis, S.V.J. Ponniah, the form master, wild elephants and white

whales could not have dragged me to school. And that's just what happened, but

that's another story for the moment. To be admitted to the Victoria Institution

in those educationally muddled-up days was an honour or a prideful achievement,

as the case may be, which would naturally hang over the heads of the lads as a

nimbus until they departed with their Cambridge certificates to conquer other

lesser terrain. The shine hardly wore off, not even under the infra-dig ragging

Victorians might have been subject to in Singapore.

nwillingly' certainly did not apply in my case, though by

the time I got to Senior One in 1950 and had to come face to face with my

Victorian nemesis, S.V.J. Ponniah, the form master, wild elephants and white

whales could not have dragged me to school. And that's just what happened, but

that's another story for the moment. To be admitted to the Victoria Institution

in those educationally muddled-up days was an honour or a prideful achievement,

as the case may be, which would naturally hang over the heads of the lads as a

nimbus until they departed with their Cambridge certificates to conquer other

lesser terrain. The shine hardly wore off, not even under the infra-dig ragging

Victorians might have been subject to in Singapore.

For my part, since I had only completed the primary classes first in Singapore and then in Klang, apart from some months in 1942 and 43 trying to memorize in vain the inevitable anthems:ki mi ga yo, miyo to ka yi no..., and the popular hits: ashita awa maabe eyo...and sakura [errr... excuse my French] and other military tunes while "training" apparently to become a zumo professional, I had as a War-time inhabitant of Sungei Rengam no means by which to pierce the formidable shield erected by the VI-founders around its academic portals. As such my surprise was/is as great as yours to find myself in 6A in January 1947. I found my way into the VI by offering/sacrificing a cockerel and a dozen whole eggs! I can assure you my face is sheer dead-pan right now, though yours might appear somewhat distorted (pardon the expression) as on a runaway madly-spinning Ferris wheel.

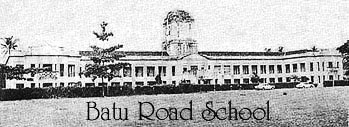

In November 1945, we moved from the ulu to the capital, as my maternal uncle, our protector during the "interregnum", decided that the Open University of the Sungei Rengam Rubber-Estate was putting certain unsettling ideas into my and my siblings' heads. Whatever was done to enrol me and my brother in a school proved futile. So, in January, in utter desperation when school was in full swing, my mother decided to give the "old" tried-and-tested Oriental method a chance. (I'm told this method still works wonders thereabouts!) It was quite a feat in those days rounding up a five-pound cockerel and a dozen eggs. Come Monday morning in the middle of January 1946, the cockerel was bound-up legs and wings; the eggs were solidly wrapped in newspaper folds forming a funnel-shaped container, and I was bundled off with each in either hand. Destination: Batu Road School.

The beak of the cockerel kept pecking holes in my spindly legs, and the eggs I held close to the chest were getting cooked or rather hard-boiled between the already singeing sun and the hotplate of my bony rib-cage. My mother reckoned it should take me about an hour to get to the school from Vanar Kampung, near the Klang bridge.

"Don't hang about the road, and don't put the eggs down", she warned in Tamil, while she tried in vain to calm the cockerel down which kept remonstrating by flapping its wings and letting off bits of feathery fur straight into my nostrils. And every time I sneezed, the cockerel was enlivened into another spate of flapping remonstrance. "Remember! You must put these in the hands of the man! No-one else! Remember!" she made me promise. I was only too well aware of the precious cargo I was lugging.

What should have taken me about an hour, actually took more than two hours. For one thing, I had to pause for breath to take the ache out of either hand, change five-pound cockerel to left or right hand every twenty yards or so. I had to hold the beast head down but not with my arms down, for its head dragged along the surface of the road. Even then, I might have made it on time by eleven o`clock, but for the armada of queries I had to put up with on the way. Everybody I knew, on cycle or waiting for a bus, or walking on the other side of the road, took it upon himself to approach me and ask me:

"Why?" - clenched fist raised and shaking about the ear, "Why, going back to market? Hen, no good, ah?" (You`ll kindly remember the Central Market was in the centre of town.) And the normally inquisitive inquirer would generally set about examining the bird by pulling at its wings and its cockscomb, which would only re-animate the beast`s sense of rebellion at being made the object of a give-away.

As the cockerel was a fine fighting home-grown specimen, I couldn`t quite answer the question to each and everybody`s satisfaction. So, I had to think up on the spur of the moment all kinds of explanations, like: "present for cousin`s wedding", or "returning present given by enemy relatives long not on speaking terms", or "refusal to accept barang-barang in lieu of money lent." With the result, I quickly backtracked from Brickfields Road and took the roundabout way via the less-frequented Travers Road to town. The stately tall palm-lined way past the Museum, the Railway HQ, Tanglin Hospital, and Selangor Club (I can assure you I`m not left-handed!) was a pleasant and airy promenade though a bit steep at first, but as I got closer to the Collesium and the Odeon, my heart started to beat faster, for I was certainly going to make a couple of stops to memorise the posters and ogle at the stars (the female variety, of course!).

By the time I reached Batu Road School, my throat was parched, and I was dying to take a leak, almost membobos to be frank. What with both my hands tied up with eggs, on the one hand, and the cockerel, in the other, it would have been a veritable feat if I could have managed it without drenching my one-and-only greenish-khaki short pants. At first, I was a bit frightened to enter the compound lest someone or other stopped me to ask: "Mari sini Inche! What think this Sunday market, ah? Market, Kampung Baru, lah! Go sana lah!" I imagined the kebun said that; he while working on the two-lane mud-track leading to the school eyed me suspiciously, and just as conveniently stopped working and leant leg akimbo on his changkul. It took me a good five minutes before I reached him, five minutes of "paid leave" for him.

"Where go?" he queried. He took his songkok in his right hand and scratched his balding sweating scalp with his free mud-stained thumb. I had difficulty getting my Adam's apple to move. It was stuck half-way down my gullet.

"Go see Tu-aa- n," I managed the magic word not without some pain. At the mention of the Headmaster`s name, he suddenly came to attention, stopped fanning himself with his imitation silk songkok, and still while riveting his eyes on my cockerel pointed to a one-storey dilapidated once-green wooden box of a house with verandah on stone pillars. I thought to myself there must have been a stream of other children, now at school, carrying similar produce. All kinds of feathered fowl roamed the dry dusty mud terrain surrounding the head`s quarters a little to the right of where I stood, some fifty yards away from the grimy-looking pre-war painted walls and low porch of the regulation two-storey H-shaped school. A lone bare cherry tree stood like a sentinel without arms or headgear in front of the house.

I had to stand some full fifteen minutes at the foot of the broken-down front stone stairs with grass growing in the crevices before the window on the verandah opened. A fair-skinned plumpy Indian-looking woman with a naked infant astride her hip and another child hanging on an arm came into view. She took one look at me and the fare in my hands, and said: "Dey! Don' wan' nothingk todaiy. Alre'dy had morning, all lah."

"Not sell cock, jes wan' see Head," said I, feeling quite disabused with the task my mother had entrusted me with. Of course, I thought my mother had not much sense giving away our best cockerel. Now the next generation of walking birds in our Vanar Kampung was sure to be depleted, stunted chicks. The lady in the purple magnolia-print cotton frock with frets for borders suddenly, it appeared, got the message.

"Leave barang. Yai keep inside. Head kaam lunchin' house," she entreated, shaking her hips like an Egyptian belly-dancer repeatedly to keep the infant from whining. Her manner appeared even cordial. "What name? Fudher?"

"No-NOO!" I retorted stubbornly, shaking my head vigorously; the cockerel also woke up at the same time and joined in the rebellion. "Can' give cock!" I was an obedient child in those days, obeyed my mother to the letter, I did. The lady's face blackened a bit. She wanted to say something and choked.

"Alrai'!" she affirmed; then she started: "Dey! Wait there! Head kaam lunchin` choon!"

I waited under the spare cherry tree, my grip on the cockerel grown numb, my head reeling under the midday sun, and I wondered how I was going to get an education in the capital at the age of twelve, having had practically none before that. My maternal uncle who tried his best to get me enrolled in a school, just any school, had to give up in utter despair. I didn`t mind grazing cows, rearing goat kids, and fowl, but not ducks for they made too much noise, and not geese -certainly not - for they invariably took me for a pecking bag full of sweet potatoes. An hour must have gone by, for when the Head in a chequered sarong and drenched dirty-white banion finally emerged from the front verandah, he was reeking of chicken curry. He must have crept into the house by the back or side entrance when I was ruminating on my non-existent educational career.

He was very business-like. He took everything for granted. He came down the stairs, and said: "Cock already dead, ah! No good, lah!" and he tugged at the cockscomb. The poor beast though in no better shape than I was managed to cough up a few dry cackling sounds.

I think it said: "Gobbledegook!" Just once. Now what could this mean?

"Hmmn!" said the Head, "Still alive!" A sleek shiny roguish crow in the cherry tree, sitting and watching the proceedings, mocked and caw-cursed raucously. Then he exclaimed, "Okay, what's that?" He prodded the egg-funnel with his forefinger.

"This for you a'so." He smiled and asked for my father`s name. I gave my mother's name.

He started: "What? Got no father, ah?" I shook my head. For a moment I thought he was going to give my cockerel back, but I was mistaken. He surveyed me. Then he climbed back up with the presents and called out to the lady in the house who took the burden off his hands and disappeared with them. I was in a frenzy. I didn't know what to do, or what to say. This was my first makan belanja deal.

"How do you spell your name?" He made as if to copy down my name with his forefinger on his forearm. Hope came back into my sunken dried-up soul. I spelt the name out.

"What class?" he whipped out.

" Er... er..Standard One, Two..., Sir," I replied, as though I was already admitted.

"Okay, tomorrow at eight o`clock. Come to my office." I was so elated, I had difficulty holding my you-know-what back. More than thirst which raked my insides, I had to let water out. He waved me off. I took a few steps and started to run to tell my mother the news when I remembered my brother. I ran back just when he was locking the front door and yelled almost out of breath:

"My brother, my brother, Sir. He he he a`so!" The Head came out onto the veranda, a look of pain creeping into his narrowing eyes. He scratched his chin and pulled on his right ear-lobe.

"What class?"

"Standard three." He cocked his head to reflect I thought. The few moments of anxiety had me in a rush of sweat.

"Okay, okay, eight o`clock sharp." He fondled his bulging mid-rift. "Don't forget, tomorrow!" And he cleaved the air with a pointing finger: "Sharp!" I went back of the cherry tree, and you know what I did; only the crow seemed amused.

Then, I ran all the way back with the good news. On the way, I stopped to drink from a gardener's water-hose left spouting on the flower bed in the roundabout between Suleiman Building and the Railway Station.

To think that if the Head didn't like chicken curry, I might never have become a Victorian! Well, you can call that Victoria's luck, for sure! Just suppose, he was a mutton curry addict... you wouldn't be blessed enough to be reading this! - for how d'ya think a twelve-year old could have borne a live goat around his shoulders and legged it across the capital in peak traffic time with bullock-carts and rickshaws and tri-shaws and pillion-heavy bicycles charging down the splintered and fractured post-war tar roads? All said and done, I wasn't feeling too elated then. The valiant sacrifice of the cockerel left lots of hens frustrated and in cackling fury both in Vanar and the Sikh kampungs in the lean post bellum years!

In those immediate days after the War, going to school was not only a hazard, but a risk to one's life itself [cf. Victimes16]; it was equally so just being in school for the duration of the classes and/or during extra-curricular activities, a veritable danger both to mental and to physical health. It all depended on who suddenly - from out of no-where (some who laid in wait for you) stalked your steps - accompanied you to school, or who - once you were there - followed you to the lavatory! One enjoyed extraordinary luck on one count though: swimming was regulated on a class basis, and therefore the "gay prowlers" could not suddenly stalk you under water. I know what you're thinking: "Well, he's at it again! Just fibbing, the Ol' So-an'-So!" Everything I recount in these columns is the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, based on fact (give or take one or two details due to memory erasures and/or literary embellishments), on what transpired on haloed Victorian ground! And that's why this new episode might sound like sacrilege given the enormous reputations the school fathered since the War.

Whether this aspect of Malaysian-hood was to be found rooted in the locally-nurtured genes is a matter that can - and perhaps should - be argued over by geneticists (including gay scientists of course); despite laws bent on punishing gay aspirations, the fact remains that over a century of British over-lordship in the region might have encouraged - even unofficially promoted - what in Imperial metropolitan territory has long enjoyed the status of a "pastime" or "sport". How many indeed the Malaysio-Singaporeans who could testify to this truth, a truth that has repeatedly caused them to retrace their steps to "Gayland" since Independence! [One well-known divorced Victorian father is known to make repeated trips to England ever since he was called to the Bar, for the call to British manly-arms still nostalgically recalls his honeymoon trip to Paris with his half-Jewish Beau during his Inns of Court dining days! Some Victorians indeed have acquired the knack of running with the hares and hunting with the hounds in this manner!] How many indeed the houseboys of the local Vicar, the peons of the Colonial administrator, all unsuspecting youths from the ulu taken under protective wings of the urbane master race whose penchant for males-only clubs or fraternities, fathered similar traditions in the protected states and colonies, the haloed tradition extending into the Imperial colonial armed forces; this penchant for exclusive male-only clubs enshrined even in Haymarket at the heart of Empire! Let's leave aside for a moment the thesis that hen-pecked husbands are expected to rear sons prone to becoming victims, or that child victims are precisely those who eventually turn pedophilic, like the Belgian specialist supplier of made-to-measure victims for those in power.

Time: Early 1947. Setting: The east wing ground

floor, adjacent to the swimming pool. Later, scene shifts to the Lake Gardens.

Protagonists: 13-year-olds (not the fourteen to seventeen year-olds)

in 6A.

Antagonists: 18-year-olds or more from the upper classes.

When the sun was but a white blotch in the blinding sky, the road bordering the east wing was the most frequented by the lonely, especially those boys without pocket money to hang around the tuck shop. There, the acacia and rain trees offered cover from prying eyes. Convenient place also where one could prepare for the exam after interval. For the gay prowlers from the senior classes, this was virgin territory to explore. The thirteen-year old was the virgin the eighteen-year old prowler shadowed, until it was time to make a call at the lavatory. Head full of memorized facts for oncoming tests, the virgin of course was oblivious of the hawk swooping down for the preliminary peck at the prey. No sooner you were up against the marble troughs, a low gruff voice next to you would attempt, by giggling, to make a joke of: "Constant dripping wears out the hardest stone!", and he would lean across to bare some yellowish disarranged teeth. You would of course give off innocent laughter at hearing what was probably the password/phrase for Victorian gays. Before you could button-up and get back into class, the gay prowler - now turned, very appreciative and concerned friend - would make his play.

"Aiyam looking for aaall saarts of material for the photo competition." Non-plussed, you could only look at him towering a foot-and-a-half above your head and wonder. No need to wonder for long. Even before you could enter your class, he'll whip out a pack of photos held together in his palms like a pack of cards and would start dealing. And even before you could manage to go through a few, he would conveniently push you towards the stairs and would be looking at the pictures over your shoulders while breathing hard at the same time down your open shirt buttons. You can thank your stars for the school bell which would like a thunderbolt bring our photo-maniac back to his senses. Of course, our senior pupil would refuse to take back the photos left in your hands.

"Noooonno Nooonno No. See ya aafta school." With that you were hooked for a ride. The stage was set!

Sunday morning the same week I was blanco-ing my canvass shoes in the back patio and putting them up to dry against the broken drain when my mother announced the arrival of a certain gentleman at the front door. Intrigued as I was, I never thought it would be our senior prowler in question. At first, I thought he had come to collect the photos he pressed into my hands at school. I was mistaken. He said he told me he would appear for the photo-snapping session right on at ten. He was dressed in a clean long-sleeved white silk shirt and flannel longs from under which sharp pointed suede shoes peeked. A camera in its leather holster dangled on his chest. On one of his wrists bristled a wrist-watch; can't say which, for there was a bangle on the other. He left his bronco at the foot of the front stairs. A shiny steed it was. Polished to brilliance, it shone even in the shade, and it was equipped for two speeds, a luxury in those days. The mud-guards were green in the middle and golden on either side. On the handle, an enormous bell on the right and a painted robin figure on the left. The lamp in front seemed like it had enjoyed a prestigious previous life on some Rolls Royce's fender some time before that. The seat was protected with a hand-sewn flower print cover, and the oversized carrier-bag containing the tools of his seduction-trade took up the better part of the metal pillion seat. And when he wheeled the bronco around, pizzicati sounds bristled forth, one note after another tumbling on the preceding pluck and giving off enough hum to mesmerize and put to sleep prospective victims. Our prowler sure laid it all on thick!

I just couldn`t say no, not after his taking the trouble to come all the way from Sentul to Brickfields. My mother only asked me if I knew him. I said, yes, and that he was a school-mate. She saw no harm in all that photo business. I was glad when he said that he wouldn`t proceed to shoot right there, for I was a bit shy of playing the model right in my kampung, in front of all the boys and girls of my age. He wanted to get out of the village enclosure; so I walked along the musically ticking bike without realizing in my innocence that I was being taken for a ride!

Once on the tar road, he insisted I get on the metal bar between the handle and the seat, for he said we'd have to find a suitable place for the snapping session. I don't know how I let him talk me into it, for no sooner he started to pedal, I felt cornered and felt his over-enveloping presence. I told him several times that I wanted to get down, but he kept on pedalling, and I realised I was in a sort of bind from which I would need more than brains to escape. Jane, the Vias's sister, on whom all the youngsters of the region had a crush - including me of course - was casually seated under the porch at her place when she suddenly jumped up at the sight of me cringing on the bicycle bar. I'd swear if I failed to win her from that day on, it was primarily on account of what she saw on that fateful Sunday morning. No more could I dream: "Me, Tarzan, you, Jane!"

He took the left turning up the steep Travers Road panting while lifting himself from the seat. I was only worried if the Ratnams would see me. He was deaf to my protestations, and I didn't want to create a scene lest it attract more attention. Once he got past the overhead railway bridge, he swirled to the right and went into high gear. There was no way I could stop him then without getting myself into a serious accident. So I just held on, knowing he would have to slow down at the foot of the Lake Gardens. But when we arrived near the Damansara turning, he started pedalling in a fury to get up the slope. And I was virtually crushed in a crouch against the handle. We were now well past the rows of wooden quarters on Travers Road, and there was no one around. What got me was the sweat and odours. I couldn't stand any more of that, and I managed to jerk the handle violently enough for him to nearly crash down the monsoon drain. Out of balance and out of the rider's breath, the bike came to a halt, tilting its occupants.

"What the hell you doing!" I yelled, sprawled on the tar road. The man was sweating profusely and his chest kept heaving almost painfully, I thought. "Go on you bugger! I`m going home!" By the time, I collected myself and was about to get back home, he suddenly began to ooze with apologies and kindnesses.

"I came so far, really, so far, lah! Jes, one or two pictures and right, I'll go," he said, almost self-pityingly, his gruff voice turning somewhat squeaky at that moment. "Next month comes the photo competition," he insisted and produced a newspaper cutting from his back pocket.

"Okay, then, take," I said, feeling rather sorry for him.

"Thanks, lah!" He looked around and pointed to a mound between some bushes up the entrance to the Lake Gardens. I was already regretting having to agree, but at the back of my mind the thought of having a photo or two of myself didn't seem a bad idea after all, especially as I had only a couple of pictures taken before that age. So we moved up to the selected backdrop, and he started to click, coming up several times to me to make me look this way and that. Thank goodness, the place was deserted. I would have died of shame playing the model in idyllic scenery like in one of those far-too-many gooseflesh-turning Bollywood or Tamil screen musicals.

I thanked him, I think, and I was about to go when he said he thought the pictures wouldn't come out well, or even not at all. I stood and listened. He said the light was not quite right. The sun shone directly into the lens.

"Must take more, lah. Otherwise, no go. Sure face will be black, lah." He kept fumbling with the lens and averted my eyes. So I thought why not. He said we'd have to go a bit higher up, and before I knew it, we were in a sort of enclosed arbour: bougainvillea bushes in bloom, plantain trees in full fan and Arabian palms thrusting about their fronds boastfully. "Here, here, nice lah." He made me sit. And between clicks came up to adjust my spindly legs and arms with as much care as placing knives and forks on tables.

I could hardly see him. I had to squint. The sun's rays poured through the fronds to blur my vision. And then it suddenly happened. He put the camera down beside the bicycle and came up to where I was seated. I thought he was going to make me pose again. Without any warning he lunged at me. I could only see a huge blotch of a shadow grow bigger and nearer. In a fraction of a second, it was all over.

Right in the nick of time I managed to avoid the lunge and rolled over. He reached out at me, but I kept rolling down the mound and bolted. But he caught up with me to assure me he wouldn't bother me any more. He kept his word though, I must say. I met him later on in cordial circumstances when he worked as a doctor in a hospital.

If I had not been such an inveterate swimmer at the VI pool where to survive one had to avoid the heedless divers from the diving boards, I might today be walking up and down the Champs Elysées with placards in support of the "gay" cause while shouting slogans for the passing of the Pax legislation, a recent French law legalising gay unions! No aspersions cast on consenting gays, of course!

© T. Wignesan January 3, 2001, Paris

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 8 June 2001.

PageKeeper:

Chung Chee Min

cheemchung@gmail.com