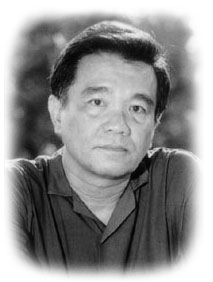

Born in September 1935 in Kuala Lumpur, Wong Phui Nam had his early education at two Chinese schools in Kuala Lumpur's Chinatown. He later joined the Batu Road School and from there went to the V.I. in 1949. Even while he was in the V.I in the morning, he was attending private classes in classical Chinese in the afternoon, boning up on Tang poetry and the Three Character Classic. He was also interested in music in his school days and took up the violin. This spawned an exhaustively researched front cover article on 300 Years of Violin Music in a 1954 issue of the school's fledgling Seladang, of which he was the literary sub-editor. This musical interest was also extended to the V.I. Society of Drama, where he selected and played the background music for the school plays Twelfth Night (1953) and Henry IV Part I (1954). Phui Nam was also a sub-editor of the Victorian.

He was equally adept on the V.I. sports field; as a Class 2 boy, he actually broke the school high jump record during the 1954 School Sports. Only trouble was that two others, including Jimmy Wong the eventual winner, also broke that same record and beat him into third place! He was secretary to Loke Yew House which he represented in swimming and table tennis. He passed his University Entrance exam that same year and joined the University of Malaya in Singapore to read for his B.A. (Hons) degree in economics.

Phui Nam had dabbled in poetry while at the V.I. but had not shown his works to anyone. At the University there was active discouragement towards writing poetry by his western lecturers - "How could you presume to use the English language?", was their argument. Still, Phui Nam was inspired by the Singapore poet Edwin Thumboo who had just published his first work Rib of Earth and so he began to read whatever he could lay his hands on. In addition, Phui Nam edited the student journal The New Cauldron. He was later chiefly responsible for two anthologies Litmus One: Selected University Verse, 1949-1957 and Thirty Poems.

On graduation, he became an Assistant Controller of the Industrial Development Division of the Ministry of Commerce in Kuala Lumpur. Later he had a stint in Bangkok as an economist and, on completing that, he joined the MIDF where fellow Victorian Tun Ismail Mohamed Ali was chairman. After ten years he left, first for a private company, and eventually joined the Malaysian International Merchant Banking Ltd. After he retired in 1989 as its general manager, he wrote a poetry column for The New Straits Times and taught briefly at a private college. He is now a training and marketing consultant in a private company.

Most of the poems Phui Nam wrote during the sixties first appeared in Bunga Emas, an anthology of Malaysian literature edited by fellow Victorian T. Wignesan. They were subsequently collected in book form and published as How the Hills are Distant in 1968 (Tenggara Supplement) by the Department of English, University of Malaya. Phui Nam remained relatively silent throughout the 1970s and the early 1980s. In 1989 his second volume Remembering Grandma and Other Rumours was published by the English Department, National University of Singapore. His Ways of Exile was published in 1993 by Skoob.

Phui Nam's poems have also appeared in Seven Poets, The Second Tongue, The Flowering Tree, Young Commonwealth Poets '65, Poems from India, Sri Lanka, Singapore and Malaya. He was also published by literary journals like Tenggara, Tumasek, South East Asian Review of English.

His mature poems are regarded as among the best Malaysian poems in English, unsurpassed in their eloquence and linguistic richness. Most of them are contemplative and draw their images from the local landscape. Wong Phui Nam's poetry explores the experience of living in multi-cultural Malaysia. "Before the British set up this country, Malaysia was a totally agrarian society," he says. "Suddenly we get this commercialism and development of plantations to supply a metropolitan power. Even for a writer in Malay, whether he is a Malay or a non-Malay, he has to reinvent the language. All the more so for Indians and Chinese. For a Chinese, when we write in Chinese, we cannot pretend that nothing has happened and try to write Tang poetry. So for us to write in English, we are exiled three times, culturally and spiritually from China, culturally from the indigenous Malay culture and then writing in English. We cannot claim that it is a tradition. I would say we have appropriated the language. So, in a way, it is a much more interesting medium to work with, to work with the language against the tradition.

"All over the world, poetry has no leading audience," says Phui Nam. "When a poet writes, he addresses his own views. When a reader reads his poem it is as if he is in a position to overhear what is written. As far as a practical public audience is concerned, a poet has to be content with maybe a few hundred all over the world, or if you are lucky, a few thousand who really enjoy poetry and find pleasure in reading what you have written. That's all most poets can hope for."

Following is How the Hills are Distant, a version from T'ao Yuan-ming and some selections from Nocturnes and Bagatelles. Perhaps Wong Phui Nam's audience will now be multiplied many, many times more.

How the Hills are Distant

i

When I am dead

and the old man, the river,

after a night of rain among the hills

should come upon me,

I shall only stir

like stones that drag the muddy bed.

When I am dead,

should the old man rage

and relieve himself upon the fields,

my heart shall no more

be taut with kneading

that works from silt green protuberant heads.

The old man grows,

lives from subconscious hills,

sentient in fishes and the reeds that slant

towards eloquence of words.

The waterfowl cry

his flowering of vowels on the wind.

If like you, old man,

I should never die

but learn my way about the hills,

I should be glad

always of rain

till the bunds of my body break and are washed in sand.

ii

The river grows harsh at the bend:

speech broken onto boulders, tears at root ends

of strong reeds. A lizard moves

and crawls in the mimosa

which spread and trail leafless

across the rough stones of my heart.

This is not the season

when the wind blows wet

and in the night rumours of the waterfowl

but of the lonely sun

when anger withers on the stony bank,

its branches bare

against the sky that holds your absence.

iii

With such violence as shattered walls of rain

when the sky's torpor broke, heavy for its slate,

the storm drags up a broken afternoon

of cowed trees and houses, and, from the fields,

the mud invades our doorsteps. The light slants,

splayed against the tree tops of the old estate,

and some of the trees put out tentative boughs of glory.

At the hilltop the house stands, shadows

etching their intents across bare faces,

touching the fringes only of vague ambiguities.

As afternoon heightens, the heart surges

with scatters of swallows soaring into deep sky.

In full flowering by the gate, the crinum lilies fountain

inconclusive into the after-light, when I withdraw

to be indoors, the heart to be within the body's house.

iv

The mist drifting across the field

edges up the compound of my house

along the foot of the hibiscus hedge,

moving vaguely like fear among the cane.

I sit up to watch, as I have on many nights

from my darkness at the window,

my heart precise within these walls,

my room with its table and crumpled bed.

It is imminent; in the sudden smell

of wet grass and stir among the frangipani,

in the straight tense fence-posts in half-light

against the margin of encroaching sleep,

where I anticipate only a wakening

to vague remembrance of a harrowing in my dream.

v

No ghosts inhabit those dark trees by the hill -

only the passing of a habitual rain,

mist, white at evening, drifting down

across the field and shallow streams.

Nothing but is fugitive. As light fades

into the whitewashed back garden fence posts

that ward off an outer darkness,

the dogs keep up their howling for the hour

before an early moon is down.

There are no ghosts here for us,

no ghosts through whom the land may give us of itself.

Its signs are a withheld mystery.

All that we may intimate from it goes no further

than a little falling of damp earth,

or a slight cold wind heard in some late hour

haunting the darkness deep within the trees.

Keeping its days and seasons,

the land yields nothing of its speech to us,

no fading echoes from the ghosts of those before us who died,

leaving us faint hints for the ear and tongue.

Against the rain nothing of the memory of our dead

is caught and held among the roots.

The merbok in the shift of weather in a passing cloud

makes for the mute stones and trees their words.

vi

I feel out of the verges of the swamps

in the body's tides, out of the bones

of an ancient misery,

the dead stir with this advent of rain;

and in a landscape long held

in the contours of anguish,

hedges and barbwire

catch the glimmer of their subdued presences.

Moving across the grass

in the numbness of a field, in the darkness

held in between our houses,

they breed in the heart a hint of primal horror.

In the settling cold, I reach

beyond distances of a train's cry,

beyond the mind's immediate neighbourhood

where the wind makes much of a tree in pain

The dead come without a history in this shifting rain,

and leave no trace in our habitation, our private landscape.

In the light of morning

upon a fallen hillside and mud about

the hedges in a suburb without memory,

they will bring no change of heart

and no hint for new rooflines.

Word of the terrible dragon's descent

upon a neighbouring hill will pass

into the breaking prism of the rain,

leaving house and suburban roads in the cold and wet

and nothing to plague the dreams of precocious children.

In the rain's passing, I stare upon the quiet,

the mild hysteria of lallang, green under street lamps.

vii

There is no rumour as you would hear,

coming too late

in neither time nor place for terror

but the quiet streets

and clocks keeping their hours

above the repetitive street lamps in a town asleep;

no rumour as you would hear,

only that the lorongs turn

from the emptiness to twist about their dark,

articulate sometimes with violence

which has only brute recognition of the body s blood;

nothing of the imagined echo

that people were open to

when stones were known to prate.

There can be no rumour that terror is in the trees

or n the water below the bridge you cross

in the early light of morning,

having come in a time and place

too late to happen on claw marks upon the pavement,

or hear of a legendary half-beast

on certain nights clamber out of the municipal fountain.

This is only a body I possess,

a body that bears a heart

weighted by its own necessity, and lost

in such a time and place

among a people who when they came

already had their demons

die the sterile deaths of gods;

so too their legendary kings.

The branch of cut lime

hung by my amah by the door

dangles therefore lightly in the breeze.

Yet do not believe

we do not have our kings;

do not believe

we take them lightly either.

We have our ways of submission

Although, one having died,

our water does not turn bitter,

only the clerks glad of one day off.

The wind does not whimper.

You will not suddenly come upon him

around a corner, looming large

in the haze of a lamp.

Only, we have our ways of submission.

A few remember when we were small

how the dragon came,

and the floods

three months after the funeral of the king.

viii

Notebook Entry Singapore, January 1962

Even the film-makers will have to admit,

the Malay annals upon the people's consciousness

would wash like the tide

piling jetsam upon the jetty steps,

you said, as the car hit

ninety, beetling into the obsessive shell

of a parched landscape. And K.L. hours behind.

Dodging the disappearances and appearances

of the road, the cradled ego growing blind

against the body's chafing would hide

from the terrible squashing of the sun,

threshing in daydream played out in the street...

of the Capitan China, the one

who, befogged in private vision,

laid down his law and had his women,

drove through the town in his carriage and eight -

for our forefathers left much behind

bringing mostly, when they came, the body

to contend with, did not notice the landscape,

the nodding vacuity of a malformed head.

At year's end, the sense of annunciation touched only

the windows of the solitary.

And at the garden party, the bishop,

between meeting the community's leaders,

picked at his beard, thinking perhaps of his study,

colonnades the cathedral town...

The Capitan s horses go clip-clop,

passing like the breeze down the midnight streets.

Our conversation petering out... silences...

Daydreams settle into laterite and gibberish of vegetation,

which made nonsense of Saint Francis' mission.

De Sequiera s troops over the ridge

forgot the meaning of their Christ and King.

Under the flare of the sun's declension

the hills ignited. We passed the region

of the dead, the circular descent of those

who died and had committed nothing.

Our room's on the second floor.

I am rather tired after today;

I feel the darkness of Babylon at the door.

ix

Broken off from their daily pre-occupations,

the streets on Sunday settle into their presences of stone.

Houses under a manic sun put up their distressed faces,

and trees along the edges of a public lot

die quietly into themselves. The city, white with dust,

has lain too long in the sun of its own inconsequence.

It is withered of saving dreams, its places

of our local habitation lie exposed,

unprotected by the blessings of spirits

from malevolent presences that lurk

under the gloom of trees in neglected gardens,

by old houses, and at odd corners of the town's back streets.

That saving dreams should die, withered

from the places where we would walk,

the buildings carry symptoms of our particular hell.

We are a people grown querulous of good news,

while no good news can come of this ill season.

You who would yet be prophets, who look for signs

and starve in a wilderness of stone, there are only boulders

drowning in pits here of worked out mining leases.

From the main street of the town,

see how the hills are distant, locked in their silences.

x

Too long about this neighbourhood has palled

the mind to reaches of the suburban rail track

bearing trains to nearby and expected places.

In this climate of our beliefs, the landscape settles

into a featureless grey and rust of blukar and laterite

that see no flowering even under mild rain.

Once, coming to these suburbs by night, the heart

was crowded as all the public houses in the town,

the streets uneasy at the coming of a strange birth.

Terror then was real as the helter-skelter in the streets

and the uproar in resisting the king's soldiery at the door.

The weather out here has drained all passions

that move upheavals preceding promise, preceding redemption.

After the violence, one becomes merely fretful

and eyes the neighbour's wife. On a clear night,

the houses show up homely behind their hedges.

Driving on the roads that aimlessly lead

from one to another, there is with me the strange beast,

somnolent and indifferent to the stars that ignite

heart s phosphorus, disintegrating towards the west.

xi

I watched the dawn flowering out of a long wound

in the sky s side. Across the anguish of rooftops,

a few trees lighten from shadow into the hardness of day,

their branches and their leaves metal against my heart

still raw from dream. At my window, I watched

a scattering of swifts spiral, tugging against tentacles

in the streaks of cloud, and I too was unwilling for the dawn -

when I must feel discovered like the city, its fastnesses, drains

open, delineated like veins. In the blood of the people's sleep,

the beast turned over on its side and groaned.

As the hour struggled towards fruition in the sun,

buildings grew tall with my oppression, and I thought

of the many recalled, the broken and the poor in spirit

scoured from the yielding womb of darkness.

I knew there was weeping, secret by the cataracts of the heart,

that has nothing of the sadness of rivers and small rain,

mist making lyric all the low trees in the field,

the heart admitting only a purgatory paved of our familiar streets,

columns and walls of buildings lit, harsh in the devouring sun.

xii

Where the blind fringes of my words

let in the symptoms of a dawn

breaking its anguish

over the hard indifferent pavements,

and loneliness in the bone engenders

this grotesquerie of faces under street lamps,

women who pace their incarceration in empty streets,

I may be ready for the torment which infects

a new beginning: to be my lute's flame

to charm these manic buildings, the columns

and mindless walls, withholding monsters,

kindling the lost ease of swaying boughs

and swifts under a mild sun, to sue

out of a paranoiac darkness for a forgotten eurydice.

xiii

Rimbaud

From the first, when the fire would no longer catch,

you, out of the doused flames,

the dried blood smoking in your face

from the damp logs, the pyre of your vision,

would emerge, not the magus invoking

new flowers, new stars, new flesh, and languages,

the fierce, the charred mute

upon whom the flesh would always close again

to feel the inevitable fresh shock

of the rain's invasion, the abstract hunger

of pavements outside the tall cathedral door

and hear the express ravening in from the suburbs,

from sunsets behind chimneys where flowering clouds of angels

darken into demons from a hell opening into your sleep.

xiv

You who have prospected a little and gone

a little of the way beyond the back fences

of homes without a history, the rail track, and old estate

with its shallow streams and found certain indications:

a change of colour in the soil,

the sudden scream of passing bird making huge

your anxiety upon the hill slopes, and then

a heart given to less frequent changes to clement weather,

beware - beware that you do not chance upon the hunger

that has taken prey of the time, come upon the hidden places

where desolation uncoils within your bowels

and rises magnified, sheer against the hill face:

the death the cobra bears for the lonely, who know no consolation,

take care that such death does not work within your bones.

xv

The Inquisitors

When they shall come again,

I do not know

where I shall hide in this consciousness

that makes distant, in this vast

plain of the damp floor

under the cell's black and foetid sky,

the congealed lotuses of my pain

dangling from the nails of my fingers,

and in my bowels, the stiff bright sword.

When they shall come again,

I will feel anew the uselessness

of weeping. In the crumbling of houses

in my first destruction,

I knew there were children too among the ruins.

Yet there are times

the wind sings sweetly in the head,

and I whimper among the boughs

of dark unreason, when

it wakens upon the ripples of mining pools.

I will be beaten down to their will,

my thoroughfares despoiled by their instruments.

Out of the ruins and re-opened tombs,

I will not see you come and go out in the streets

to tell the lame to walk and the blind to see.

You will not be there

when I am hunted out among my childhood -

there will only the relief of darkness

from the body's distant habitations

across the vast plain of the floor

and the cell s foetid sky.

xvi

To him only the despair is real,

rising from the face against the steep steps

upward to the overwhelming hill

of Calvary. It deadens the long deep strikes of pain

into the shoulder, as the dragged heavy end

of the cross knocks in the teeth

of the steps following the ascent.

The mean fact of houses crowds the way

leaning upon the lonely self,

their rough walls whitening into a forgetfulness

that night of fearful weeping in the garden.

There is only desolation in the midst of fire,

as the planted crown strikes root

into breaking skin and skull.

The agony beats back the overhanging Roman sun

and the multitude pressing in upon the hour

told in the eventual silence of the indifferent sky.

To those who, after, turn away,

there cannot be richly laden vineyards on the slopes,

but a dry wind sawing at ruined walls

and a hint of bones in its tracks across the sands.

xvii

For a birthday

To be most myself is to be

this darkness that pervades the land,

to be this foul weather that invades

the turning wooden back stairs climbing up

to my place of rainless sleep, and in the morning,

in the small hours of the soul,

the cold that comes making large

the doorways. The body in its spell

is a scatter of small stones beneath the porch.

This then is a country that one cannot wish

to be. The spirit not given its features

festers in the flesh, incites the year

to come upon it like the tiger. The city's parks,

odd street corners, and the public buildings

bear the stench, the torn fur

of trivial remembrances. Thus in the flesh

am I hunted out, creature of my days,

vocal perhaps to seem some kind of Job

tending my sores to an emptiness,

the hoarse throat my psaltery to make such sounds

as may breed some hint of the soul's endurance.

Who would be comforters, do not begin to dress

or even touch these scabs.

Their peeling leaves

a spreading terrain,

where all conclusions, all arguments are broken down

to miles of striations, the soft mudflats.

xviii

Words for an epiphany - for Wignesan

I am the pitiful christ nailed

to my birth

here, where they have no use for causes

or the agony I become,

redeeming nothing,

waking

to this brutal residue of stone

after the epiphany

of the body's pain, the dog

dragging its broken hind legs

from the road -

I, the lost christ

among the fumes of the town s back streets.

Let the locomotive jump its rails

and houses fall...

I will make dices of their finger-joints,

these legionnaires

gaming for shirt and sandals.

I strangled my mother-in-law

bearing the futility of it all,

the anguish of useless conversations

at coffee tables, in hotel beds,

against the opening darkness of the town's back streets.

Let the locomotive jump its rails

and houses fall....

xix

Batu Lane, K.L. - for Wignesan

...And suddenly the lane opens onto a settlement.

Till now I could not have guessed

I would find myself wandering on a warm night

among so many in this foetid maze of hovels,

lost in a fog of moist intent

caught from the must and stale scent of women

in closed rooms. I find myself among the dead

who yet have not died to their hungers,

returning to this ruined world in search

of bodies, of unprotected human hosts.

Till now I had not thought that

there could be so many unprotected in the world,

so many It is useless to feel for so many,

for so many of the unprotected women in this fallen world.

Grown indifferent to their flesh, they sit on low stools,

or on their haunches by their hovels,

silent, or hurt behind loud conversations.

When in a slant of light from a doorway

you catch the eye of one; behind

the stiffening of the face, you see the crouched,

helpless, the stunted unfinished creature.

a moment, and she is gone - behind preparations

she raises against the assault upon her body,

under her red-eyed, hostile stare.

xx

There is upon the beachhead of my sleep

a beating tide that tolls for the cast up, unburied dead.

And faintly in the air, the dying among seaweed

hear a massing of scavengers, a raucous gathering

of a hungry choir. The few that come up choking

on their vomit for the violent rollers in the dream

will find no gods here to propitiate, no shrines

at which to place flowers and bowls of fruit,

burnt offerings to prick the nostrils of the gods

that they may waken into pity for their plight.

Only shadows inhabit the island, and they know

no gods. Inland the terrain is locked tight in salt,

where beasts and fowl, and snakes in the dust

and crystals lay down their bones by bitter lakes.

There are no journeys but into the noon s madness,

or into the chill hysteria of the night.

Moving in a habitation among shadows,

there can be, for them, no tales but a recounting of losses.

This is a time to endure camping upon lonely beaches,

to be content not to take too much stock

by shooting stars auguring the advent of sails.

A Version from T'ao Yuan-ming

(A.D. 376-427)

I

I had no taste, when young, for the world's affairs, my heart native to the love of hills. For thirteen years now I am fallen, tangled in the deep snares of the world. A caged bird is haunted by the old, dark woods, in shallow ponds the fish, their former waters. And so, I have returned to farm upon the margins of the southern wilds - my land, a bare two acres and my house, ruled into eight rooms or perhaps nine, with the elm and willow leaning thick upon the eaves, and in the court, the planted peach and plum. The dwelling places of men are away in the distance wreathed thinly with the smoke from market towns. One hears only the barking of dogs among deep lanes, the cocks crowing, hidden among the mulberry tops. I am no longer visited with the world's desires, my days made over with such large and ample ease. My heart, long caged and corralled, assumes now the major freedom of the hills.

II

In the wilderness where men's affairs are absent, the narrow lanes empty of passing horse and carriage, and houses remain shuttered in the sun, I have put away my flesh's and the world's desires. And at the times when the farmers gather or meet by chance, going about in their grass capes in the fields, they have but few words for each other. Now is the season when the crops planted daily find increase and the season when my purposes daily are fulfilled; of anxiety at the coming frost and sleet when as the tangled vegetation, I shall stand ruined and bare.

III

My bean rows grow sparsely under the southern hill, strangled and choked by the coarse devouring weeds, though I toil all day upon the wilderness, from daybreak till darkness falling, when I grope my way home by the moon. The footpath is narrow with overhanging weeds. My clothes are wet from the risen dew. But then I should not care that my clothes are wet when it is my purpose not to care.

IV

It has been a long time since I went among the hills and marshlands, where in the solitude, the wild untrammelled weeds and trees pleased my heart, and I found my peace. I, an old man, must leave my children and those of my children's generation, and with a staff of hazelwood in hand, wander once more about the wilds. Once in a desert place, I came upon a profusion of mounds and broken dykes about the habitation of a people of an earlier time. There were wells, choked and fallen in, and kitchens, broken open to the wind and rain. The straggles of bamboo and mulberry grew meanly over the untended ground. When I asked of a passing wood-gatherer, he made in reply: All the people here have perished, man, woman, and child, never to return. A generation passes like a market fair. Truly, the living are but passing tricks and shadows, and a return to nothingness, our end.

V

I returned alone by the broken tortuous trails, my heart full of the mountain's desolation. At a torrent, where the stream was bright and shallow, I washed my feet. I strain the clear and new-made wine, and with a capon serve my guests. At the going down of the sun we light brushwood to serve as candles. Cloistered with the living joy of friends how quickly the bitter dark will pass. And then ... a new daybreak.

Nocturnes and Bagatelles

II

from Tu Fu: Tonight, a full moon, and you alone again. I think often of the children, too young to feel my absence here at Ch'ang-an. Your hair must be laved with the dew and your limbs cold. I do not know when I can return ... to be with you behind the empty curtains, the tear-stains on our faces bright in the moon.

III

from Li Po: At my bed's feet my room ignites, white with the moon's loneliness. And I feel outside, the cold, incendiary in the hard frost upon the ground. I am full of the moon, on looking up, hanging large above the window, and in my dark, I meet, on looking down, my fierce unsatisfied longing to be home.

IV

The river grows harsh at the bend, speech broken onto boulders, tears at root-ends of strong reeds. A lizard moves and crawls in the mimosa which spread and trail leafless across the rough stones of my heart. This is not the season when the wind blows wet and in the night rumours of water fowl but of the lonely sun when anger withers on the stoney bank, its branches bare against the sky that holds your absence.

VIII

from Tu Fu:

A slender moon is setting among tree-tops

of the prowling wind.

We sit, ambushed

in the lute's dark melody,

our clothes long wet with the risen dew.

The flowers grow tall

in the ministering dark, and among the skeins of grass,

the stars.

The night burns, too short

like a scholar's candle,

for our ensuing talk of swords and embroidery, among wine-cups,

our verse, recited

moves with the lightness of a skiff

passing, and returns upon the mind.

X

Rummaging among my thoughts I went down their steps to the cellar with a bundle of words as matches to throw up areas of light upon the clammy walls, and I left my shadow at the door, substanceless, unheard. Here were the tangles of my childhood - half-dreams propelled, lifting the trap-door off my heart, me on the violence of the garden swing - twitching like half-torn snakes, buried in part. It seemed, from the light where bushes felt really green with the familiar air of a well-off merchant, I have been summoned by unformed voices I left behind to come to the cellar to set my house in order to rationalise in neat parcels, the sky that turned like a bald face over the circular garden-walk over the child on the swing who gave his orang-outang identity, its irrational leer behind bougainvillea stalks.

XI

for my old amah:

To most your dying seems distant

outside the railings of our concern.

Only to you the fact was real

when the flame caught among the final brambles

of your pain. And lying there

in this cubicle, on your trestle

over the old newspapers and spittoon,

your face bears the waste of terror

at the crumbling of your body's walls.

The moth fluttering against the electric bulb,

and on the walls the old photographs,

do not know your going. I do not know

when it has wrenched open the old wounds.

When branches snapped in the dark

you would have had a god among the trees

who made us a journey of your going.

Your palms crushed the child's tears from my face.

Now this room will become your going, brutal

in the discarded combs, the biscuit tins

and neat piles of your dresses.

XIII

I must make self-murder that I live,

cauterise love at the root of sense

till deceit and all that pain

wither with body's recalcitrance.

But words alone do not resurrect

dog that wets the bottom of those steps.

I must make self-murder that I live,

and batter ego in his bed

till deceit and all that pain

be out with heart on which it bred.

But words alone do not resurrect

dog that wets the bottom of those steps.

That soul should elbow its way

and not stay clear

leaving, for all its neighbourliness

the body harder to bear,

that of body I should sour

its giving of itself

rape sense and throw it out-of-doors

making it more stubborn by half,

transmute of this brawl the shards

into formal pain of words.

And words alone will not resurrect

dog that wets the bottom of those steps.

XIV

That he cared a little less for his habitual image of himself, the bamboo hedges and the tall palms leaped with the sudden flame of morning. That he should acknowledge pain of unfinished lineaments the cannas unfurled, yellow and huge in unaccustomed freedom and the play of sparrows among thick leaves would serve for words. The distance unwound itself of muscular clouds, unwound his guard over his secret places of inadequacies. The hills with hidden water-courses and valleys bearing rain came close to his touch. From the fire the gardener lit in wet piles of grass, the smoke hung all day beneath the trees.

The V.I. Web Page

The V.I. Web PageLast update on 22 July 2008.

Page-Keeper: Chung Chee Min